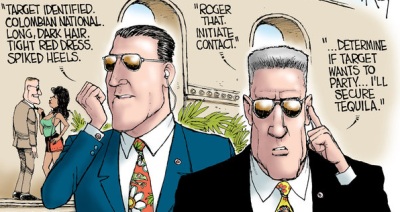

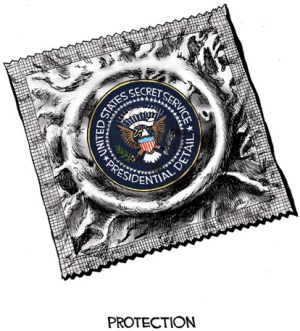

Secret Service agents like high class hookers????

If you ask me all victimless crimes, including prostitution should be legalized.My problem is when government hypocrites enforce these laws against us serfs, but think that they are above the laws and break them as these Secret Service agents are accused of doing.

Misconduct alleged against Secret Service agents

Apr. 13, 2012 09:55 PM

Associated Press

CARTAGENA, Colombia -- A dozen Secret Service agents sent to Colombia to provide security for President Barack Obama at an international summit have been relieved of duty because of allegations of misconduct.

A caller who said he had knowledge of the situation told The Associated Press the misconduct involved prostitutes in Cartagena, site of the Summit of the Americas. A Secret Service spokesman did not dispute that.

A U.S. official, who was not authorized to speak publicly on the matter and requested anonymity, put the number of agents at 12. The agency was not releasing the number of personnel involved.

The Washington Post reported that Jon Adler, president of the Federal Law Enforcement Officers Association, said the accusations related to at least one agent having involvement with prostitutes in Cartagena. The association represents federal law enforcement officers, including the Secret Service. Adler later told the AP that he had heard that there were allegations of prostitution, but he had no specific knowledge of any wrongdoing.

Ronald Kessler, a former Post reporter and the author of a book about the Secret Service, told the Post that he had learned that 12 agents were involved, several of them married.

The incident threatened to overshadow Obama's economic and trade agenda at the summit and embarrass the U.S. The White House had no comment.

Secret Service spokesman Ed Donovan would not confirm that prostitution was involved, saying only that there had been "allegations of misconduct" made against Secret Service personnel in the Colombian port city hosting Obama and more than 30 world leaders.

Donovan said the allegations of misconduct were related to activity before the president's arrival Friday night.

Obama was attending a leaders' dinner Friday night at Cartagena's historic Spanish fortress. He was due to attend summit meetings with regional leaders Saturday and Sunday.

Those involved had been sent back to their permanent place of duty and were being replaced by other agency personnel, Donovan said. The matter was turned over to the agency's Office of Professional Responsibility, which handles the agency's internal affairs.

"These personnel changes will not affect the comprehensive security plan that has been prepared in advance of the president's trip," Donovan said.

U.S. Secret Service agents leave Colombia over prostitution inquiry

SourceU.S. Secret Service agents leave Colombia over prostitution inquiry

By David Nakamura and Joe Davidson, Published: April 13

The U.S. Secret Service is investigating allegations of misconduct by agents who had been sent to Cartagena, Colombia, to provide security for President Obama’s trip to a summit that began there Friday.

Edwin Donovan, an agency spokesman, said that an unspecified number of agents have been recalled and replaced with others, stressing that Obama’s security has not been compromised because of the change. Obama arrived in Cartagena on Friday afternoon for this weekend’s Summit of the Americas, a gathering of 33 of the hemisphere’s 35 leaders to discuss economic policy and trade.

Donovan declined to disclose details about the nature of the alleged misconduct. But Jon Adler, president of the Federal Law Enforcement Officers Association, said the accusations relate to at least one agent having involvement with prostitutes in Cartagena.

In a statement, Donovan said the matter has been turned over to the agency’s Office of Professional Responsibility, which serves as the agency’s internal affairs unit.

“The Secret Service takes all allegations of misconduct seriously,” Donovan said. “These personnel changes will not affect the comprehensive security plan that has been prepared in advance of the President’s trip.”

Adler said the entire unit was recalled for purposes of the investigation. The Secret Service “responded appropriately” and is “looking at a very serious allegation,” he said, adding that the agency “needs to properly investigate and fairly ascertain the merits of the allegations.”

The Washington Post was alerted to the investigation by Ronald Kessler, a former Post reporter and author of several nonfiction books, including the book “In the President’s Secret Service: Behind the Scenes With Agents in the Line of Fire and the Presidents They Protect.”

Kessler said he was told that a dozen agents had been removed from the trip. He added that soliciting prostitution is considered inappropriate by the Secret Service, even though it is legal in Colombia when conducted in designated “tolerance zones.” However, Kessler added, several of the agents involved are married.

There have been other incidents involving Obama’s security detail over the past year.

In November, Christopher W. Deedy, a federal agent with the State Department’s Bureau of Diplomatic Security, was charged with second-degree murder after shooting a man during a dispute outside a McDonald’s in Honolulu. Though Deedy was off-duty at the time, he was on the island to provide advance security arrangements for Obama’s trip to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit.

In August, Daniel L. Valencia, a Secret Service agent, was arrested on suspicion of drunken driving in Decorah, Iowa, where he was helping arrange security for Obama’s bus trip through three Midwestern states. Valencia, who was off-duty at the time of the arrest, was recently sentenced to two days in jail with credit for time served, and a fine of $1,250.

South American governments want to end drug war!!!

South American governments want to end drug war!!!Of course the American government is going to stick it's head in the sand and pretend we are winning the insane, unconstitutional drug war.

At Latin America summit, Obama to face push for drug legalization

By Christi Parsons and Brian Bennett, Los Angeles Times

April 13, 2012, 4:45 p.m.

CARTAGENA, Colombia — President Obama will highlight trade and business opportunities in Latin America at a regional summit in Colombia this weekend, but other leaders may upstage him by pushing to legalize marijuana and other illicit drugs in a bid to stem rampant trafficking.

Obama, who opposes decriminalization, is expected to face a rocky reception in this Caribbean resort city, which otherwise forms a friendly backdrop for a U.S. president courting Latino voters in an election year. But the American demand for illegal drugs has caused fierce bloodshed, plus political and economic turmoil, across much of the region.

Colombia's president, Juan Manuel Santos, wants the 33 leaders at the Summit of the Americas to consider whether the solution should include regulating marijuana, and perhaps cocaine, the way alcohol and tobacco are. Other member states also are calling for that dialogue despite the political discomfort it may cause Obama back home.

"You haven't had this pressure from the region before," said Michael Shifter, president of the Inter-American Dialogue, a think tank in Washington. "I think the [Obama] administration is willing to entertain the discussion, but hoping it doesn't turn into a critique of the U.S. and put the U.S. on the defensive."

Obama also is expected to take flak from leaders frustrated by the lack of U.S. movement on two other troublesome issues, immigration reform and the long-standing embargo of Cuba. Cuban leaders are not participating in the summit, but many regional governments oppose the U.S. policy of embargo.

In internal debates, White House officials have weighed the risk of talking about decriminalization, which is still taboo for many U.S. voters, against concern about alienating leaders who bear the brunt of the battle against the heavily armed cartels that supply most marijuana, cocaine and methamphetamines to U.S. markets.

White House officials say Obama will not change his drug policy. They hope to keep talk of legalization behind closed doors while he focuses publicly on other tactics, including improving security forces, reforming governance and enhancing economic opportunities.

The call for change comes from front-line veterans of the drug wars, including Colombia. Santos says he has the moral authority to seek new solutions because his country's citizens and security forces have spilled so much blood fighting drug traffickers.

Also leading the charge isGuatemala'spresident, Otto Perez Molina. After a pre-summit meeting with leaders of Costa Rica and Panama, he called for a "realistic and responsible" discussion of decriminalization in Cartagena.

"We cannot eradicate global drug markets, but we can certainly regulate them as we have done with alcohol and tobacco markets," he wrote in the British newspaper the Observer on April 7.

White House officials plan to argue that no evidence indicates legalization would slow the flow of narcotics or reduce drug-related killings. Vice President Joe Biden offered a preview in Miami Beach last month.

"We should have this debate, and the reason is to dispel some of the myths that exist about legalization," Biden told reporters. "There are those people who say, 'If you legalize, you are not going to expand the number of consumers significantly.' Not true."

U.S. officials also will emphasize administration efforts to reduce illicit drug use in the United States, the world's largest consumer of cocaine and other illegal drugs.

The Justice Department, for example, has added special courts that can sentence drug abusers to treatment programs instead of prison. And the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, assuming it survives Supreme Court review, requires the medical industry to treat substance abuse as a chronic disease.

Marijuana use in America has increased by 15% since 2006, but cocaine use has dropped by 40% in that time, according to theU.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Experts say the global market for cocaine is unchanged because use in Europe more than doubled in the last decade.

The idea of regulating and taxing the production and sale of illegal drugs isn't new. A panel led by former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan and past presidents of Mexico, Brazil and Colombia concluded in a report in June that the drug war had "failed" and recommended easing penalties for farmers and low-level drug users.

That doesn't make the issue any easier for Obama.

"I don't think anybody thinks the current policy works right now, but public opinion hasn't gotten to the point of accepting the idea of legalization," said David Damore, a political scientist at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas who writes about U.S. and Latino politics. "There's nothing to be gained from it politically, and it opens you up to an attack."

cparsons@latimes.com

brian.bennett@latimes.com

Parsons reported from Cartagena and Bennett from Washington.

The US is alone on it's stance to continue the insane unconstitutional drug war, which is a dismal failure.

The US is also alone on it's stance to isolated Cuba from the rest of the world.

I suspect this quote by H. L. Mencken is one of the reasons for America's political positions:

U.S, Canada alone on Cuba at summit

by Vivian Sequera - Apr. 14, 2012 10:32 AM

Associated Press

CARTAGENA, Colombia -- A summit of 33 Western Hemisphere leaders opens Saturday with the United States and Canada standing firm, but alone, against everyone else's insistence that Cuba join future summits.

The Sixth Summit of the Americas has also taken on a tabloid tinge with 12 U.S. Secret Service agents sent home for alleged misconduct that apparently included prostitutes and days of heavy pre-summit poolside drinking.

U.S. President Barack Obama has been clinging stubbornly to a rejection of Cuban participation in the summits, which everyone but Canada deems unjust.

"This is the last Summit of the Americas," Bolivia's foreign minister, David Choquehuanca, told The Associated Press, "unless Cuba is allowed to take part."

The fate of the summit's final declaration was thrown into uncertainty Friday as the foreign ministers of Venezuela, Argentina and Uruguay said their presidents wouldn't sign it unless the U.S. and Canada removed their veto of future Cuban participation.

Vigorous discussion is also expected on drug legalization, which the Obama administration opposes. And Obama will be in the minority in his opposition to Argentina's claim to the British-controlled Falkland Islands.

The charismatic Obama may be able to charm the region's leaders as he did in 2009 with a pledge of being an "equal partner," but he will also have to prove the U.S. truly values their friendship and a stake in their growth.

"The United States should realize that its long-term strategic interests are not in Afghanistan or in Pakistan but in Latin America," the host, Colombian President Juan Santos, said in a speech to business leaders at a parallel CEO summit on Friday.

In large part, declining U.S. influence comes down to waning economic clout, as China gains on the U.S. as a top trading partner. It has surpassed the U.S. in trade with Brazil, Chile, and Peru and is a close second in Argentina and Colombia.

"Most countries of the region view the United States as less and less relevant to their needs -- and with declining capacity to propose and carry out strategies to deal with the issues that most concern them," the Washington-based think tank the Inter-American Dialogue noted in a pre-summit report.

Stereotypes of ugly Americans were, unfortunately, reinforced on summit eve with misconduct allegations

A caller who alerted The Associated Press to the case said the misconduct involved prostitutes.

A Secret Service spokesman did not dispute that. Nor did the U.S. official who, speaking on condition of anonymity because of the matter's sensitivity, put the number of agents sent home at 12. The agency was not releasing the number of personnel involved.

One employee of the hotel where the agents stayed, the beachfront Caribe, said the agents drank large quantities of alcohol at the poolside daily for about a week before being dressed down by a supervisor and sent home Thursday. The employee spoke on condition of anonymity because he feared for his job.

Obama faced challenges enough at the summit without that distraction.

Cuba was proving the biggest.

Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa was boycotting the summit over Cuba's exclusion, while moderates such as Santos and President Dilma Rousseff of Brazil said there should be no more America's summits without the communist island.

Obama's administration has greatly eased family travel and remittances to Cuba, but has not dropped the half-century U.S. embargo against the island, nor moved to let it back into the Organization of American States, under whose auspices the summit is organized.

Another big issue will be drug legalization, which the Obama administration firmly opposes. Santos left it off the official agenda but has said all possible scenarios should be explored and the United Nations should consider them.

Meeting with Argentine President Cristina Fernandez at his request, Obama can expect to discuss that country's claim to the Falkland Islands, known as the Malvinas by the Argentines, after Argentina lost a war with Britain 30 years ago while trying to seize them.

Among the hemisphere's leaders, there is nearly unanimous support for Argentina's position.

One potentially prickly confrontation for Obama was averted Saturday when Venezuela's foreign minister announced that President Hugo Chavez would skip the summit. The minister, Nicolas Maduro, said Chavez took the decision because of a medical recommendation.

Chavez was heading instead to Cuba to continue treatments for cancer.

He has grabbed the spotlight at past summits. But, suffering from an unspecified type of cancer, he has lately been shuttling back and forth to Cuba for radiation treatment.

America is out of touch with the rest of the world???

America is out of touch with the rest of the world??? I think so!!!

"The whole aim of practical politics

is to keep the populace alarmed (and

hence clamorous to be led to safety)

by menacing it with an endless series

of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary."

Of course two of those hobgoblins are the "drug war" and Communistic Cuba, along with the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Secret Service scandal deepens

Source

Secret Service scandal deepens

11 agents, 5 military members involved

by Libardo Cardona - Apr. 14, 2012 11:28 PM

Associated Press

CARTAGENA, Colombia - An embarrassing scandal involving prostitutes and Secret Service agents deepened Saturday as 11 agents were placed on leave, and the agency designed to protect President Barack Obama had to offer regret for the mess overshadowing his diplomatic mission to Latin America.

The controversy also expanded to the U.S. military, which announced that five service members staying at the same hotel as the agents in Colombia may also have been involved in misconduct. They were confined to their quarters in Colombia and ordered not to have contact with others.

The alleged activities took place before Obama arrived Friday for meetings with 33 other regional leaders.

Put together, the allegations were an embarrassment for an American president on foreign soil and threatened to upend White House efforts to keep his trip focused squarely on boosting economic ties with fast-growing Latin America. Obama was holding two days of meetings at the Summit of the Americas with leaders from across the vast region before heading back to Washington tonight.

The Secret Service did not disclose the nature of the misconduct. The Associated Press confirmed on Friday that it involved prostitutes.

The White House said Obama had been briefed about the incidents but would not comment on his reaction.

"The president does have full confidence in the United States Secret Service," presidential spokesman Jay Carney said when asked.

Carney insisted the matter was a distraction more for the media than for Obama. But Secret Service Assistant Director Paul Morrissey said in a statement: "We regret any distraction from the Summit of the Americas this situation has caused."

Rep. Peter King, chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee, told the AP on Saturday that "close to" all 11 of the agents involved had brought women back to their rooms at a hotel separate from where Obama is now staying.

The New York Republican said the women were "presumed to be prostitutes" but investigators were interviewing the agents.

King said he was told that anyone visiting the hotel overnight was required to leave identification at the front desk and leave the hotel by 7 a.m. When a woman failed to do so, it raised questions among hotel staff and police, who investigated. They found the woman with the agent in the hotel room and a dispute arose over whether the agent should have paid her.

King said he was told that the agent did eventually pay the woman.

The incident was reported to the U.S. Embassy, prompting further investigation, King said

The 11 in question were special agents and Uniformed Division officers. None was assigned to directly protect Obama. All were sent home and replaced, Morrissey said.

The Secret Service says the incidents have had no bearing on its ability to provide security for Obama's stay in Colombia.

The U.S. Southern Command said on Saturday that five service members assigned to support the Secret Service violated their curfew and may have been involved in inappropriate conduct. Carney said it was part of the same incident involving the Secret Service.

Col. Scott Malcom, chief of public affairs for Southern Command, said of the five service members: "The only misconduct I can confirm is that they were violating the curfew established." He said he had seen the news reports about the Secret Service agents involved in alleged prostitution but could not confirm whether the service members also were involved.

The military is investigating.

The Secret Service agents had stayed at Cartagena's five-star Hotel Caribe.

A hotel employee, speaking on the condition of anonymity for fear of losing his job, said the agents arrived at the beachfront hotel about a week ago and said the agents left the hotel Thursday.

Three waiters at the hotel told the AP the agents were drinking heavily during their stay.

11 Secret Service agents put on leave amid prostitution inquiry

Source11 Secret Service agents put on leave amid prostitution inquiry

By David Nakamura and Ed O’Keefe, Published: April 14

The U.S. Secret Service on Saturday placed 11 agents on administrative leave as the agency investigates allegations that the men brought prostitutes to their hotel rooms in Cartagena, Colombia, on Wednesday night and that a dispute ensued with one of the women over payment the following morning.

Secret Service Assistant Director Paul S. Morrissey said the agents had violated the service’s “zero-tolerance policy on personal misconduct” during their trip to prepare for President Obama’s arrival at an international summit this weekend.

“We regret any distraction from the Summit of the Americas this situation has caused,” Morrissey said in a statement.

The rapidly unfolding scandal has upstaged Obama’s trip to the summit, where he is discussing trade and the economy with 32 other heads of state. Though the agency has said Obama’s security was not compromised, the allegations of misconduct have brought intense scrutiny to an agency that had not had a major lapse since 2009, when two party crashers entered the White House uninvited.

The situation deteriorated further Saturday when the Defense Department announced that five military personnel, who are staying at the same hotel, violated curfew Wednesday night and have been confined to their rooms. The department will conduct its own investigation upon their return to the United States, said Air Force Gen. Douglas Fraser of the U.S. Southern Command, where the military personnel were from.

Fraser said he was “disappointed by the entire incident and . . . this behavior is not in keeping with the professional standards expected of members of the United States military.”

Rep. Peter T. King (R-N.Y.), chairman of the Homeland Security Committee, said Saturday that Secret Service officials conducting an internal investigation told him that the staff at the Hotel Caribe summoned local police after discovering a woman in the room of one agent after 7 a.m., against the hotel’s policy for visitors of paying guests.

Although the agent eventually paid the woman and she left, King added, police reported the incident to the U.S. Embassy, which informed the Secret Service. The agency quickly recalled the agents and replaced them with a new team before Obama’s arrival Friday afternoon at the Hilton a few blocks away.

King praised the agency for removing the men involved, but he added that “everything they did was a violation of proper conduct.”

“First of all, to be getting involved with prostitutes in a foreign country can leave yourself vulnerable to blackmail and threats,” King said. “To be bringing prostitutes or almost anyone into a security zone when you’re supposed to protect the president is totally wrong.”

Briefing reporters in Cartagena, press secretary Jay Carney said the White House learned of the incident Thursday and Obama was informed Friday.

“This has not been a distraction,” Carney said. “It has been much more so for the press than for the president, who is going on with his work here.”

The Hotel Caribe is in Bocagrande, a seaside district of Cartagena. It’s not a colonial hotel, like those in the old walled city, but rather an elegant, decades-old structure that is considered a national patrimony. Locals consider it a good place to party — there is a beachfront bar-restaurant in front of the hotel and inside it has gardens and bars.

Any presidential trip, but especially those abroad, involve immense manpower and logistical planning that can take place weeks before the president arrives, experts said.

Typically, on a foreign trip, more than 200 federal officials from the Secret Service, Defense Department and White House staff are sent to the site two weeks ahead of the event. Once the president arrives on Air Force One, usually with a support plane and press charter plane in tow, an additional 200 people or more join the original group.

Several people familiar with the Cartagena investigation described a night of partying by members of the advance team, who created enough of a disturbance in the Hotel Caribe that hotel employees asked the group to quiet down more than once.

Prostitution is legal in Colombia, but soliciting women for paid sexual favors is against Secret Service policy. It is not clear how many of the 11 agents, some of whom are reportedly married, had sexual encounters with the women or whether it was clear to all of them that the women expected to be paid.

One person with close ties to the Secret Service, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to speak freely about an ongoing investigation, said he was told by agents that the woman involved in the dispute “freaked out” after she was not paid and banged on walls and doors in the hotel hallways.

But King described a calmer scene. He said that under hotel policy, any overnight guest of a paying guest must leave photo identification at the front desk and leave the hotel by 7 a.m. the next morning.

According to King, one of the 11 women had not left the hotel by 7 a.m. Thursday, prompting hotel officials to knock on the door of the room. When nobody answered, hotel officials summoned police officers, King said.

Once police opened the door, the woman and the agent had a brief dispute over payment, King said, but the agent eventually paid the woman and she left.

Colombian police made no arrests because prostitution is legal in the country, but they turned over to the embassy a list of U.S. personnel staying at the hotel.

King said U.S. Secret Service Special Agent in Charge Paula Reid, based in Miami, rushed to remove the officers from the country Thursday.

Ralph Basham, director of the Secret Service from 2003 to 2006, said he spoke with current agency Director Mark J. Sullivan, and Basham called the agents’ alleged conduct “totally out of bounds.” But Basham defended the agency’s quick action in removing the agents from Cartagena.

“Clearly, they made a huge mistake,” he said. “But to try to tie this somehow to impacting the security of the president of the United States is just outrageous. It did not.”

Staff writers Joe Davidson, Peter Finn and Scott Wilson and correspondent Juan Forero contributed to this report. Wilson and Forero reported from Cartagena.

Prostitute scandal: '20 or 21' women involved, officials say

I could care less if government employees are humping prostitutes. And for that matter I would prefer that the folks in the military be humping hookers instead of murdering woman and children in Afghanistan and Iraq.The problem I have with this is our government masters are always giving us the "do as I say, not as I do" line of BS. It's OK for them to hump prostitutes, but they want to put us serfs in jail when we hire a hookers.

Also I am pretty angry about the one Secret Service agent who tried to cheat his hooker out of the money she earned. Again, our government masters will quickly put us serfs in jail if we don't pay our bills, but here is a police officer working for the Secret Service who cheats a prostitute out of her hard earned wages.

Prostitute scandal: '20 or 21' women involved, officials say

Apr. 17, 2012 11:55 AM

Associated Press

WASHINGTON -- At least 20 foreign women and as many Secret Service officers and Marines met at a hotel in Colombia in an incident involving prostitution, and lawmakers are seeking information about any possible threat to the U.S. or to President Barack Obama who arrived for a conference soon after, congressional officials said Tuesday.

In briefings throughout the day, Secret Service Director Mark Sullivan told lawmakers that 11 members of his agency met with 11 women at a hotel in Cartagena and that more foreign females were involved with American military personnel.

Obama and some key congressional Republicans, meanwhile, said they continued to support Sullivan.

"The president has confidence in the director of the Secret Service. Director Sullivan acted quickly in response of this incident and is overseeing an investigation as we speak in to the matter," said White House spokesman Jay Carney.

Sullivan shuttled between meetings with lawmakers Tuesday, outlining what his investigators in Washington and in Colombia have found about the incident.

"Twenty or 21 women foreign nationals were brought to the hotel," Sen. Susan Collins, the ranking Republican on the Homeland Security Committee, said Sullivan told her. Eleven of the Americans involved were Secret Service, she reported, and "allegedly Marines were involved with the rest."

Meanwhile, Sullivan told the chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee that the 11 Secret Service agents and officers were telling different stories to investigators about who the women were. Sullivan has dispatched more investigators to Columbia to interview the women, said Rep. Peter King, R-N.Y.

"Some are admitting (the women) were prostitutes, others are saying they're not, they're just women they met at the hotel bar," King said in a telephone interview. Sullivan said none of the women, who had to surrender their IDs at the hotel, were minors. "But prostitutes or not, to be bringing a foreign national back into a secure zone is a problem," King said.

The scandal overshadowed Obama's visit to a Latin America summit over the weekend and embarrassed the U.S.'s top military brass. Pentagon press secretary George Little said that military members who are being investigated were assigned to support the Secret Service in preparation for Obama's official visit to Cartagena. He said they were not directly involved in presidential security.

The Secret Service sent 11 of its members, a group including agents and uniformed officers, home from Colombia amid allegations that they had hired prostitutes at a Cartagena hotel. The military members being investigated were staying at the same hotel.

The Secret Service personnel were placed on administrative leave, and on Monday the agency announced that it also had revoked their security clearances.

Lawmakers in both the House and Senate are looking into the allegations, with King's committee devoting four investigators. He said it's not yet clear whether he'll call hearings on the matter. He, too, said he's standing behind Sullivan.

Yea, sure you can get a fair trail. The Federal Court system is just as corrupt and unjust as the Arizona courts are! In fact one man may have been falsely executed because of the corrupt FBI crime labs.

I suspect getting a "fair trial" in the American criminal injustice system is about

as easy as going to Las Vegas and willing a billion dollars!!!!

Honest! Maybe even a little bit easier!

Convicted defendants left uninformed of forensic flaws found by Justice Dept.

By Spencer S. Hsu, Published: April 16

Justice Department officials have known for years that flawed forensic work might have led to the convictions of potentially innocent people, but prosecutors failed to notify defendants or their attorneys even in many cases they knew were troubled.

Officials started reviewing the cases in the 1990s after reports that sloppy work by examiners at the FBI lab was producing unreliable forensic evidence in court trials. Instead of releasing those findings, they made them available only to the prosecutors in the affected cases, according to documents and interviews with dozens of officials.

In addition, the Justice Department reviewed only a limited number of cases and focused on the work of one scientist at the FBI lab, despite warnings that problems were far more widespread and could affect potentially thousands of cases in federal, state and local courts.

As a result, hundreds of defendants nationwide remain in prison or on parole for crimes that might merit exoneration, a retrial or a retesting of evidence using DNA because FBI hair and fiber experts may have misidentified them as suspects.

In one Texas case, Benjamin Herbert Boyle was executed in 1997, more than a year after the Justice Department began its review. Boyle would not have been eligible for the death penalty without the FBI’s flawed work, according to a prosecutor’s memo.

The case of a Maryland man serving a life sentence for a 1981 double killing is another in which federal and local law enforcement officials knew of forensic problems but never told the defendant. Attorneys for the man, John Norman Huffington, say they learned of potentially exculpatory Justice Department findings from The Washington Post. They are seeking a new trial.

Justice Department officials said that they met their legal and constitutional obligations when they learned of specific errors, that they alerted prosecutors and were not required to inform defendants directly.

The review was performed by a task force created during an inspector general’s investigation of misconduct at the FBI crime lab in the 1990s. The inquiry took nine years, ending in 2004, records show, but the findings were never made public.

In the discipline of hair and fiber analysis, only the work of FBI Special Agent Michael P. Malone was questioned. Even though Justice Department and FBI officials knew that the discipline had weaknesses and that the lab lacked protocols — and learned that examiners’ “matches” were often wrong — they kept their reviews limited to Malone.

But two cases in D.C. Superior Court show the inadequacy of the government’s response.

Santae A. Tribble, now 51, was convicted of killing a taxi driver in 1978, and Kirk L. Odom, now 49, was convicted of a sexual assault in 1981.

Key evidence at each of their trials came from separate FBI experts — not Malone — who swore that their scientific analysis proved with near certainty that Tribble’s and Odom’s hair was at the respective crime scenes.

But DNA testing this year on the hair and on other old evidence virtually eliminates Tribble as a suspect and completely clears Odom. Both men have completed their sentences and are on lifelong parole. They are now seeking exoneration in the courts in the hopes of getting on with their lives.

Neither case was part of the Justice Department task force’s review.

A third D.C. case shows how the lack of Justice Department notification has forced people to stay in prison longer than they should have.

Donald E. Gates, 60, served 28 years for the rape and murder of a Georgetown University student based on Malone’s testimony that his hair was found on the victim’s body. He was exonerated by DNA testing in 2009. But for 12 years before that, prosecutors never told him about the inspector general’s report about Malone, that Malone’s work was key to his conviction or that Malone’s findings were flawed, leaving him in prison the entire time.

After The Post contacted him about the forensic issues, U.S. Attorney Ronald C. Machen Jr. of the District said his office would try to review all convictions that used hair analysis.

Seeking to learn whether others shared Gates’s fate, The Post worked with the nonprofit National Whistleblowers Center, which had obtained dozens of boxes of task force documents through a years-long Freedom of Information Act fight.

Task force documents identifying the scientific reviews of problem cases generally did not contain the names of the defendants. Piecing together case numbers and other bits of information from more than 10,000 pages of documents, The Post found more than 250 cases in which a scientific review was completed. Available records did not allow the identification of defendants in roughly 100 of those cases. Records of an unknown number of other questioned cases handled by federal prosecutors have yet to be released by the government.

The Post found that while many prosecutors made swift and full disclosures, many others did so incompletely, years late or not at all. The effort was stymied at times by lack of cooperation from some prosecutors and declining interest and resources as time went on.

Overall, calls to defense lawyers indicate and records documented that prosecutors disclosed the reviews’ results to defendants in fewer than half of the 250-plus questioned cases.

Michael R. Bromwich, a former federal prosecutor and the inspector general who investigated the FBI lab, said in a statement that even if more defense lawyers were notified of the initial review, “that doesn’t absolve the task force from ensuring that every single defense lawyer in one of these cases was notified.”

He added: “It is deeply troubling that after going to so much time and trouble to identify problematic conduct by FBI forensic analysts the DOJ Task Force apparently failed to follow through and ensure that defense counsel were notified in every single case.”

Justice Department spokeswoman Laura Sweeney said the federal review was an “exhaustive effort” and met legal requirements, and she referred questions about hair analysis to the FBI. The FBI said it would evaluate whether a nationwide review is needed.

“In cases where microscopic hair exams conducted by the FBI resulted in a conviction, the FBI is evaluating whether additional review is warranted,” spokeswoman Ann Todd said in a statement. “The FBI has undertaken comprehensive reviews in the past, and will not hesitate to do so again if necessary.”

Santae Tribble and Kirk Odom

John McCormick had just finished the night shift driving a taxi for Diamond Cab on July 26, 1978. McCormick, 63, reached the doorstep of his home in Southeast Washington about 3 a.m., when he was robbed and fatally shot by a man in a stocking mask, according to his widow, who caught a glimpse of the attack from inside the house.

Police soon focused on Santae Tribble as a suspect. A police informant said Tribble told her he was with his childhood friend, Cleveland Wright, when Wright shot McCormick.

After a three-day trial, jurors deliberated two hours before asking about a stocking found a block away at the end of an alley on 28th Street SE. It had been recovered by a police dog, and it contained a single hair that the FBI traced to Tribble. Forty minutes later, the jury found Tribble guilty of murder. He was sentenced in January 1980 to 20 years to life in prison.

Tribble, 17 at the time, his brother, his girlfriend and a houseguest all testified that they were together preparing to celebrate the guest’s birthday the night McCormick was killed. All four said Tribble and his girlfriend were asleep between 2 and 4:30 a.m. in Seat Pleasant.

Tribble took the stand in his own defense, saying what he had said all along — that he had nothing to do with McCormick’s killing.

The prosecution began its closing argument by citing the FBI’s testimony about the hair from the stocking.

This January, after a year-long effort to have DNA evidence retested, Tribble’s public defender succeeded and turned over the results from a private lab to prosecutors. None of the 13 hairs recovered from the stocking — including the one that the FBI said matched Tribble’s — shared Tribble’s or Wright’s genetic profile, conclusively ruling them out as sources, according to mitochondrial DNA analyst Terry Melton of the private lab.

“The government’s entire theory of prosecution — that Mr. Tribble and Mr. Wright acted together to kill Mr. McCormick — is demolished,” wrote Sandra K. Levick, chief of special litigation for the D.C. Public Defender Service and the lawyer who represents Gates, Tribble and Odom. In a motion to D.C. Superior Court Judge Laura Cordero seeking Tribble’s exoneration, Levick wrote: “He has waited thirty-three years for the truth to set him free. He should have to wait no longer.”

In an interview, Tribble, who served 28 years in prison, said that whether the court grants his request or not, he sees it as a final chance to assert his innocence.

“Ms. Levick has been like an angel,” Tribble added, “. . . and I thank God for DNA.”

Details of the new round of hair testing illustrate how hair analysis is highly subjective. The FBI scientist who originally testified at Tribble’s trial, Special Agent James A. Hilverda, said all the hairs he retrieved from the stocking were human head hairs, including the one suitable for comparison that he declared in court matched Tribble’s “in all microscopic characteristics.”

In August, Harold Deadman, a senior hair analyst with the D.C. police who spent 15 years with the FBI lab, forwarded the evidence to the private lab and reported that the 13 hairs he found included head and limb hairs. One exhibited Caucasian characteristics, Deadman added. Tribble is black.

But the private lab’s DNA tests irrefutably showed that the 13 hairs came from three human sources, each of African origin, except for one — which came from a dog.

“Such is the true state of hair microscopy,” Levick wrote. “Two FBI-trained analysts, James Hilverda and Harold Deadman, could not even distinguish human hairs from canine hairs.”

Hilverda declined to comment. Deadman said his role was limited to describing characteristics of hairs he found.

Kirk Odom’s case shares similarities with Tribble’s. Odom was convicted of raping, sodomizing and robbing a 27-year-old woman before dawn in her Capitol Hill apartment in 1981.

The victim said she spoke with her assailant and observed him for up to two minutes in the “dim light” of street lamps through her windows before she was gagged, bound and blindfolded in an hour-long assault.

Police put together a composite sketch of the attacker, based on the victim’s description. About five weeks after the assault, a police officer was talking to Odom about an unrelated matter. He thought Odom looked like the sketch. So he retrieved a two-year-old photograph of Odom, from when he was 16, and put it in a photo array for the victim. The victim picked the image out of the array that April and identified Odom at a lineup in May. She identified Odom again at his trial, telling jurors her assailant “had left her with an image of his face etched in her mind.”

At trial, FBI Special Agent Myron T. Scholberg testified that a hair found on the victim’s nightgown was “microscopically like” Odom’s, meaning the samples were indistinguishable. Prosecutors explained that Scholberg had not been able to distinguish between hair samples only “eight or 10 times in the past 10 years, while performing thousands of analyses.”

But on Jan. 18 of this year, Melton, of the same lab used in the Tribble case, Mitotyping Technologies of State College, Pa., reported its court-ordered DNA test results: The hair in the case could not have come from Odom.

On Feb. 27, a second laboratory selected by prosecutors, Bode Technology of Lorton, turned over the results of court-ordered nuclear DNA testing of stains left by the perpetrator on a pillowcase and robe.

Only one man left all four partial DNA profiles developed by the lab, and that man could not have been Odom.

The victim “was tragically mistaken in her identification of Mr. Odom as her assailant,” Levick wrote in a motion filed March 14 seeking his exoneration. “One man committed these heinous crimes; that man was not Kirk L. Odom.”

Scholberg, who retired in 1985 as head of hair and fiber analysis after 18 years at the FBI lab, said side-by-side hair comparison “was the best method we had at the time.”

Odom, who was imprisoned for 20 years, had to register as a sex offender and remains on lifelong parole. He says court-ordered therapists still berate him for saying he is not guilty. Over the years, his conviction has kept him from possible jobs, he said.

“There was always the thought in the back of my mind . . . ‘One day will my name be cleared?’ ” Odom said at his home in Southeast Washington, where he lives with his wife, Harriet, a medical counselor.

Federal prosecutors declined to comment on Tribble’s and Odom’s specific claims, citing pending litigation.

One government official noted that Odom served an additional 16 months after his release for an unrelated simple assault that violated his parole.

However, in a statement released after being contacted by The Post, Machen, the U.S. attorney in the District, acknowledged that DNA results “raise serious questions in my mind about these convictions.”

“If our comprehensive review shows that either man was wrongfully convicted, we will promptly join him in a motion to vacate his conviction, as we did with Donald Gates in 2009,” Machen said.

The trouble with hair analysis

Popularized in fiction by Sherlock Holmes, hair comparison became an established forensic science by the 1950s. Before modern-day DNA testing, hair analysis could, at its best, accurately narrow the pool of criminal suspects to a class or group or definitively rule out a person as a possible source.

But in practice, even before the “ ‘CSI’ effect” led jurors to expect scientific evidence at every trial, a claim of a hair match packed a powerful, dramatic punch in court. The testimony, usually by a respected scientist working at a respected federal agency, allowed prosecutors to boil down ambiguous cases for jurors to a single, incriminating piece of human evidence left at the scene.

Forensic experts typically assessed the varying characteristics of a hair to determine whether the defendant might be a source. Some factors were visible to the naked eye, such as the length of the hair, its color and whether it was straight, kinky or curly. Others were visible under a microscope, such as the size, type and distribution of pigmentation, the alignment of scales or the thickness of layers in a given hair, or its diameter at various points.

Other judgments could be made. Was the hair animal or human? From the scalp, limbs or pubic area? Of a discernible race? Dyed, bleached or otherwise treated? Cut, forcibly removed or shed naturally?

But there is no consensus among hair examiners about how many of these characteristics were needed to declare a match. So some agents relied on six or seven traits, while others needed 20 or 30. Hilverda, the FBI scientist in Tribble’s case, told jurors that he had performed “probably tens of thousands of examinations” and relied on “about 15 characteristics.”

Despite his testimony, Hilverda recorded in his lab notes that he had measured only three characteristics of the hair from the stocking — it was black, it was a human head hair, and it was from an African American. Similarly, Scholberg’s notes describe the nightgown hair in Odom’s case in the barest terms, as a black, human head hair fragment, like a sample taken from Odom.

Hilverda acknowledged that results could rule out a person or be inconclusive. However, he told jurors that a “match” reflected a high likelihood that two hairs came from the same person. Hilverda added, “Only on very rare occasions have I seen hairs of two individuals that show the same characteristics.”

In Tribble’s case, federal prosecutor David Stanley went further as he summed up the evidence. “There is one chance, perhaps for all we know, in 10 million that it could [be] someone else’s hair,” he said in his closing arguments, sounding the final word for the government.

Stanley declined to comment.

Flaws known for decades

The Tribble and Odom cases demonstrate problems in hair analysis that have been known for nearly 40 years.

In 1974, researchers acknowledged that visual comparisons are so subjective that different analysts can reach different conclusions about the same hair. The FBI acknowledged in 1984 that such analysis cannot positively determine that a hair found at a crime scene belongs to one particular person.

In 1996, the Justice Department studied the nation’s first 28 DNA exonerations and found that 20 percent of the cases involved hair comparison. That same year, the FBI lab stopped declaring matches based on visual comparisons alone and began requiring DNA testing as well.

Yet examples of FBI experts violating scientific standards and making exaggerated or erroneous claims emerged in 1997 at the heart of the FBI lab’s worst modern scandal, when Bromwich’s investigation found systematic problems involving 13 agents. The lab’s lack of written protocols and examiners’ weak scientific qualifications allowed bias to influence some of the nation’s highest-profile criminal investigations, the inspector general said.

From 1996 through 2004, a Justice Department task force set out to review about 6,000 cases handled by the 13 discredited agents for any potential exculpatory information that should be disclosed to defendants. The task force identified more than 250 convictions in which the agents’ work was determined to be either critical to the conviction or so problematic — for example, because a prosecutor refused to cooperate or records had been lost — that it completed a fresh scientific assessment of the agent’s work. The task force was directed to notify prosecutors of the results.

The only real notice of what the task force found came in a 2003 Associated Press account in which unnamed government officials said they had turned over results to prosecutors and were aware that defendants had been notified in 100 to 150 cases. The officials left the impression that anybody whose case had been affected had been notified and that, in any case, no convictions had been overturned, the officials said.

But since 2003, in the District alone, two of six convictions identified by The Post in which forensic work was reassessed by the task force have been vacated. That includes Gates’s case, but not those of Tribble and Odom, who are awaiting court action and were not part of the task force review.

The Gates exoneration also shows that prosecutors failed to turn over information uncovered by the task force.

In addition to Gates, the murder cases in Texas and Maryland and a third in Alaska reveal examples of shortcomings.

All three cases, in addition to the District cases, were handled by FBI agent Malone, whose cases made up more than 90 percent of scientific reviews found by The Post.

In Texas, the review of Benjamin Herbert Boyle’s case got underway only after the defendant was executed, 16 months after the task force was formed, despite pledges to prioritize death penalty cases.

Boyle was executed six days after the Bromwich investigation publicly criticized Malone, the FBI agent who worked on his case, but the FBI had acknowledged two months earlier that it was investigating complaints about him.

The task force asked the Justice Department’s capital-case review unit to look over its work, but the fact that it failed to prevent the execution was never publicized.

In Maryland, John Norman Huffington’s attorneys say they were never notified of the findings of the review in his case, leaving them in a battle over the law’s unsettled requirements for prosecutors to turn over potentially exculpatory evidence and over whether lawyers and courts can properly interpret scientific findings.

In Alaska, Newton P. Lambert’s defenders have been left to seek DNA testing of remaining biological evidence, if any exists, while he serves a life sentence for a 1982 murder. Prosecutors for both Huffington and Lambert claim they disclosed findings at some point to other lawyers but failed to document doing so. In Lambert’s case, The Post found that the purported notification went to a lawyer who had died.

Senior public defenders in both states say they received no such word, which they say would be highly unlikely if it in fact came.

Malone, 66, said he was simply using the best science available at the time. “We did the best we could with what we had,” he said.

Even the harshest critics acknowledge that the Justice Department worked hard to identify potentially tainted convictions. Many of the cases identified by the task force involved serious crimes, and several defendants confessed or were guilty of related charges. Courts also have upheld several convictions even after agents’ roles were discovered.

Flawed agents or a flawed system?

Because of the focus on Malone, many questionable cases were never reviewed.

But as in the Tribble and Odom cases, thousands of defendants nationwide have been implicated by other FBI agents, as well as state and local hair examiners, who relied on the same flawed techniques.

In 2002, the FBI found after it analyzed DNA in 80 selected hair cases that its agents had reported false matches more than 11 percent of the time. “I don’t believe forensic science truly understood the significance of microscopic hair comparison, and it wasn’t until [DNA] that we learned that 11 percent of the time, two hairs can be microscopically similar yet come from different people,” said Dwight E. Adams, who directed the FBI lab from 2002 to 2006.

Yet a Post review of the small fraction of cases in which an appeals court opinion describes FBI hair testimony shows that several FBI agents gave improper testimony, asserting the remote odds of a false match or invoking bogus statistics in the absence of data.

For example, in testimony in a Minnesota bank robbery case, also in 1978, Hilverda, the agent who worked on Tribble’s case, reiterated that he had been unable to distinguish among different people’s hair “only on a couple of occasions” out of more than 2,000 cases he had analyzed.

In a 1980 Indiana robbery case, an agent told jurors that he had failed to tell different people’s hair apart just once in 1,500 cases. After a slaying in Tennessee that year, another agent testified in a capital case that there was only one chance out of 4,500 or 5,000 that a hair came from someone other than the suspect.

“Those statements are chilling to read,” Bromwich said of the exaggerated FBI claims at trial.

Todd, the FBI spokeswoman, said bureau lab reports for more than 30 years have qualified their findings by saying that hair comparisons are not a means of absolute positive identification. She requested a list of cases in which agents departed from guidelines in court.

The Post provided nine cases.

Todd declined to say whether the bureau considered taking steps to determine whether other agents intentionally or unintentionally misled jurors. “Only Michael Malone’s conduct was questioned in the area of hair comparisons,” Todd said. “The [inspector general] did not question the merits of microscopic hair comparisons as a scientific discipline.”

Experts say the difference between laboratory standards and examiners’ testimony in court can be important, especially if no one is reading or watching what agents say.

“It seemingly has never been routine for crime labs to do supervision based on trial testimony,” said University of Virginia School of Law professor Brandon L. Garrett. “You can have cautious standards, but if no one is supervising their implementation, it’s predictable that analysts may cross the line.”

‘Veil of secrecy’

A review of the task force documents, as well as Post interviews, found that the Justice Department struggled to balance its roles as a law enforcer defending convictions, a minister of justice protecting the innocent, and a patron and practitioner of forensic science.

By excluding defense lawyers from the process and leaving it to prosecutors to decide case by case what to disclose, authorities waded into a legal and ethical morass that left some prisoners locked away for years longer than necessary. By adopting a secret process that limited accountability, documents show, the task force left the scope and nature of scientific problems unreported, obscuring issues from further study and permitting similar breakdowns.

“The government has hidden behind the veil of secrecy to shield these abuses despite official assurances that justice would be done,” said David Colapinto, general counsel of the National Whistleblowers Center.

The American Bar Association and others have proposed stronger ethics rules for prosecutors to act on information that casts doubt on convictions; opening laboratory and other files to the defense; clearer reporting and evidence retention; greater involvement by scientists in setting rules for testimony at criminal trials; and more scientific training for lawyers and judges.

Other experts propose more oversight by standing state forensic-science commissions and funding for research into forensic techniques and experts for indigent defendants.

A common theme among reform-minded lawyers and experts is taking the oversight of the forensic labs away from police and prosecutors.

“It’s human to make mistakes,” said Steven D. Benjamin, president-elect of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “It’s wrong not to learn from them.”

More specifically, the D.C. Public Defender Service, Benjamin’s group and others said justice would be served by retesting hair evidence in convictions nationwide from 1996 and earlier. “If microscopic hair analysis was a key piece of evidence in a conviction, and it was one of only a limited amount of evidence in a case, would it be worthwhile to retest that using mitochondrial DNA? I would say absolutely,” said Adams, the former FBI lab director.

The promised review by federal prosecutors of hair convictions in the District would not include cases before 1985, when FBI records were computerized, and would not disclose any defendant’s name. That approach would have missed Gates, Odom and Tribble, who were convicted earlier.

Representatives for Machen, the FBI and the Justice Department also declined to say why the review should be limited to D.C. cases. The Post found that 95 percent of the troubled cases identified by the task force were outside the District.

Avis E. Buchanan, director of the D.C. Public Defender Service, said her agency must be “a full participant” in the review, which it has sought for two years, and that it should extend nationwide. “Surely the District of Columbia is not the only place where such flawed evidence was used to convict the innocent,” she said.

Staff researcher Jennifer Jenkins and database editor Ted Mellnik contributed to this report.

Escort Recounts Quarrel With Secret Service Agent

By WILLIAM NEUMAN

Published: April 18, 2012

CARTAGENA, Colombia — A Secret Service agent preparing for President Obama’s arrival at an international summit meeting and a single mother from Colombia who makes a living as a high-priced escort faced off in a room at the Hotel Caribe a week ago over how much he owed her for the previous night’s intercourse. “I tell him, ‘Baby, my cash money,’ ” the woman said in her first public comments on a spat that would soon spiral into a full-blown scandal.

The dispute — he offered $30 for services she thought they had agreed were worth 25 times that — triggered a tense early morning struggle in the hallway of the posh hotel involving the woman, another prostitute, Colombian police officers arguing on the women’s behalf and American federal agents who tried but failed to keep the matter — which has shaken the reputation of the Secret Service — from escalating.

Sitting on a couch in her living room wearing a short jean skirt, high-heeled espadrilles and a tight spandex top with a plunging neckline, the woman described how she and a girlfriend were approached by a group of American men at a discotheque. In an account that tracked with the official version of events coming out of Washington, but could not be independently confirmed, she said the men bought a bottle of Absolut vodka for the table and when that was finished bought a second one.

“They never told me they were with Obama,” she said. “They were very discreet.”

A taxi driver who picked up the woman at the Hotel Caribe the morning of the encounter said he heard her and another woman recount the dispute over payment. When approached by The Times, the woman was reluctant to speak about what occurred. As she nervously told her story, a friend gave details that seemed to corroborate her account.

There was a language gap between the 24-year-old woman, who declined to give her full name, and the American man who sat beside her all night and eventually invited her back to his room. She agreed, stopped on the way to buy condoms but told him he would have to give her a gift. He asked how much. Not knowing he worked for President Obama but figuring he was a well-heeled foreigner, she said she told him $800.

The price alone, she said, indicates that she is an escort, not a prostitute. “You have higher rank,” she said. “An escort is someone who a man can take out to dinner. She can dress nicely, wear nice makeup, speak and act like a lady. That’s me.”

By 6:30 the next morning, after being awoken by a telephone call from the hotel front desk reminding her that, under the hotel’s rules for prostitutes, she had to leave, whatever deal the two had agreed on had broken down. She recalled that the man told her he had been drunk when they discussed the price. He countered with an offer of 50,000 pesos, the equivalent of about $30.

Disgusted with such a low offer, she pressed the matter. He became angry, ordered her out of the room and called her an expletive, she said.

She said she was crying at that point and went across the hall, where another escort had spent the night with a second American man from the same group. Both women began trying to get the money.

They knocked on the door but got no response. She threatened to call the police, but the man’s friend begged her not to, saying they did not want trouble. Finally, she said, she left to go home but came across a policeman who was stationed on the hallway and called in an English-speaking colleague.

He accompanied her back to the room and the dispute escalated. Two other Americans from the club emerged from their rooms and stood guard in front of their friend’s locked door. The two Colombian officers tried to argue the woman’s case.

A hotel security officer arrived. Eventually, she lowered her demand to $250, which she said was the amount she has to pay the man who helps find her customers. Eager to resolve the matter fast, the American men eventually gave her a combination of dollars and local currency worth about $225, and she left.

It was only days later, once a friend she had shared her story with called to say that the dispute had made the television news, that she learned that the man had been a Secret Service agent.

She was dismayed, she said, that the news reports have described her as a prostitute as though she walked the streets picking up just anyone.

“It’s the same but it’s different,” she said, indicating that she is much more selective about her clients and charges much more than a streetwalker. “It’s like when you buy a fine rum or a BlackBerry or an iPhone. They have a different price.”

The woman veered between anger and fear as she told of her misadventure. “I’m scared,” she said, indicating she did not want the man she spent the night with to get into any trouble but now feared that he might retaliate against her.

“This is something really big,” she said. “This is the government of the United States. I have nervous attacks. I cry all the time.”

The Secret Service declined to comment on the woman’s account. Among the issues under review is whether the security personnel went out that night looking for prostitutes or whether they encountered them where they had been drinking.

“There was no evidence that these women were seeking these guys out — that they were waiting for Secret Service agents — but all of that is being looked into,” said Representative Peter T. King, the chairman of the House Committee on Homeland Security.

Mr. King, who was briefed on the matter on Tuesday by Mark Sullivan, the Secret Service director, said that the Secret Service agents at the hotel had provided conflicting reports about the night’s events.

“Some of them were saying they didn’t know they were prostitutes,” he said. “Some are saying they were women at the bar. I understand that there was quite a bit of drinking.”

When a reporter read the woman’s account to him over the phone on Wednesday, Mr. King said, “Nothing you are telling me contradicts what I have been told.” He said that there was no evidence that the women obtained information about the president’s security, but he added: “That is still be looked at.”

He said that investigators believe the youngest woman involved was 20 years old.

As for cooperating with the American investigators who are seeking to interview as many as 21 different women who they believe may have spent the night with American security officers in advance of Mr. Obama’s arrival, the woman who was involved in the payment dispute said she was not interested in that. She said she was planning to leave Cartagena soon.

Michael S. Schmidt contributed reporting from Washington.

Secret Service scandal is not new

Apr. 19, 2012 12:00 AM

I worked as a military Spanish-language translator for a decade in Latin America.

I worked with the National Security Agency, Drug Enforcement Administration and various U.S. dipolomatic employees.

The behavior of the U.S. Secret Service agents and military personnel in Colombia is the norm, not the exception.

Your tax dollars at work!

-- JD Ricks, Mesa

Look prostitution is legal in Colombia and even if you think prostitution is immoral the cop should have paid the hooker what he agreed to pay her in stead of cheating her out of $575.

This really pisses me off because our government masters are always pretending to be more moral and ethical then us serfs they rule over.

Prostitute scandal: 3 Secret Service employees out

Apr. 18, 2012 04:30 PM

Associated Press

WASHINGTON -- The prostitution scandal at the Secret Service claimed its first casualties Wednesday. The agency announced three agents are leaving the service, even as separate U.S. government investigations were under way. The tawdry episode took a sharp political turn when presumptive Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney said he would fire the agents involved.

The Secret Service did not identify the three agents leaving the government or eight more it said remain on administrative leave. In a statement, it said one supervisor was allowed to retire and another will be fired for cause. A third employee, who was not a supervisor, has resigned.

The agents were implicated in the prostitution scandal in Colombia that also involved about 10 military service members and as many as 20 women. All the Secret Service employees who were involved had their security clearances revoked.

"These are the first steps," said Rep. Pete King, R-N.Y., chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee, which oversees the Secret Service. King said the agency's director, Mark Sullivan, took employment action against "the three people he believes the case was clearest against." But King warned: "It's certainly not over."

King said the agent set to be fired would sue. King said Sullivan had to follow collective bargaining rules but was "moving as quickly as he can. Once he feels the facts are clear, he's going to move."

The scandal, which has become an election-year embarrassment for the Obama administration, erupted last week after 11 Secret Service agents were sent home from the colonial-era city of Cartagena on Colombia's Caribbean coast after a night of partying that reportedly ended with at least some of them bringing prostitutes back to their hotel. The special agents and uniformed officers were in Colombia in advance of President Barack Obama's arrival for the Summit of the Americas.

A White House official said Wednesday night that Obama had not spoken directly to Sullivan since the incident unfolded late last week. Obama's senior aides are in close contact with Sullivan and the agency's leadership, said the official, who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

In Washington and Colombia, separate U.S. government investigations were already under way. King said he has assigned four congressional investigators to the probe. The House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, led by Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif., sought details of the Secret Service investigation, including the disciplinary histories of the agents involved. Secret Service investigators are in Colombia interviewing witnesses.

In a letter to Sullivan, Issa and Rep. Elijah Cummings of Maryland, the committee's ranking Democrat, said the agents "brought foreign nationals in contact with sensitive security information." A potential security breach has been among the concerns raised by members of Congress.

The incident occurred before Obama arrived and was at a different hotel than the president stayed in.

Sen. Chuck Grassley, the ranking Republican on the Senate Judiciary Committee, said news of the three agents leaving Secret Service was a positive development.

"I've always said that if heads don't roll, the culture in a federal agency will never change," the Iowa lawmaker said in a statement. "Today's personnel actions, combined with the swift removal and investigation, are positive signs that there is a serious effort to get to the bottom of this scandal."

New details of the sordid night emerged Wednesday. A 24-year-old self-described prostitute told The New York Times that she met an agent at a discotheque in Cartagena and after a night of drinking, the pair agreed the agent would pay her $800 for sex at the hotel. The next morning, when the hotel's front desk called because the woman hadn't left, the pair argued over the price.

"I tell him, 'Baby, my cash money,'" the woman told the newspaper in an interview in Colombia. She said the two argued after the agent initially offered to pay her about $30 and the situation escalated, eventually ending with Colombian law enforcement involved. She said she was eventually paid about $225.

Romney told radio host Laura Ingraham on Wednesday that "I'd clean house" at the Secret Service.

"The right thing to do is to remove people who have violated the public trust and have put their play time and their personal interests ahead of the interests of the nation," Romney said.

While Romney suggested to Ingraham that a leadership problem led to the scandal, he told a Columbus, Ohio, radio station earlier that he has confidence in Sullivan, the head of the agency.

"I believe the right corrective action will be taken there and obviously everyone is very, very disappointed," Romney said. "I think it will be dealt with (in) as aggressive a way as is possible given the requirements of the law."

When asked, the Romney campaign would not say whether he had been briefed on the situation or was relying upon media reports for details.

At least 10 military personnel who were staying at the same hotel are also being investigated for misconduct.

Two U.S. military officials have said they include five Army Green Berets. One of the officials said the group also includes two Navy Explosive Ordinance Disposal technicians, two Marine dog handlers and an Air Force airman. The officials spoke on condition of anonymity because the investigation is still under way.

Secret Service's Office of Professional Responsibility, which handles that agency's internal affairs, is investigating, and the Homeland Security Department's inspector general also has been notified.

Sullivan, who this week has briefed lawmakers behind closed doors, said he has referred to the case to an independent government investigator.

Col. Scott Malcom, a spokesman of U.S. Southern Command, which organized the military team assigned to support the Secret Service's mission in Cartagena, said Wednesday that an Air Force colonel is leading the military investigation and arrived in Colombia with a military lawyer Tuesday morning.

The troops are suspected of violating curfews set by their commanders.

"They were either not in their room or they showed up to their room late while all this was going on or they were in their room with somebody who shouldn't be there," Malcom said.

Lawmakers have called for a thorough investigation and have suggested they would hold oversight hearings, though none has yet been scheduled. The incident is expected to come up next week on Wednesday when Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano appears before the Senate Judiciary Committee for a previously scheduled oversight hearing.

House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, said that for now, he is interested in what actually happened. He did not address how much responsibility Obama should bear for the scandal or whether Congress should hold hearings on it.

Secret Service Pre-Planned Party at Colombian Hotel

By Mary Bruce | ABC OTUS News

CARTAGENA, Colombia - Secret Service officials planning a wild night of fun in Colombia did some of their own advanced work last week, booking a party space at the Hotel Caribe before heading out to the night clubs, hotel sources tell ABC News.

As first reported by ABC, the men went to the "Pley Club" brothel, where they drank expensive whiskey and bragged that they worked for President Obama. The men were also serviced by prostitutes at the club.

But the night didn't end there. The men brought women from the Pley Club back to the hotel and also picked up additional escorts from other clubs and venues around town, sources tell ABC News.

Eleven officials were involved and, according to Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, who was briefed on the misconduct by Secret Service, "twenty or twenty-one women foreign nationals were brought to the hotel."

ABC has learned that, when booking the party space, the men told hotel staff that they anticipated roughly 30 people.

The following morning there was reportedly a dispute between one of the women and an official over the amount of money she was owed for spending the night. A quarrel ensued and the authorities were ultimately called.

The officials' misconduct in Cartagena last week, ahead of the president's visit for the Summit of the Americas, has already forced three agents out of their positions.

The Secret Service announced Wednesday that one supervisor was allowed to retire while another was "proposed for removal for cause." A third, non-supervisory employee resigned. The remaining eight Secret Service personnel allegedly involved remain on administrative leave.

The Secret Service has also widened their investigation of the officials to include possible drug use during their partying in Cartagena, ABC News confirmed.

More likely to lose Secret Service jobs over scandal

By Aamer Madhani, and Kevin Johnson

WASHINGTON – A top Republican lawmaker said Thursday that more dismissals and resignations are imminent as the Secret Service continues its internal investigation into a prostitution scandal that has shaken the agency charged with protecting the president.

House Homeland Security Committee Chairman Pete King, R-N.Y., who had been briefed by Secret Service Director Mark Sullivan, said more Secret Service officials were expected to resign by today. Meanwhile, agency officials are scheduled to brief Senate Judiciary Committee staff today on the progress of the internal investigation.

The anticipated round of resignations and firings would follow the agency's announcement Wednesday that three officials involved in the scandal are leaving their posts. One official resigned. Another described as a supervisory employee was allowed to retire, and the agency moved to dismiss another supervisory employee for cause.

Lawrence Berger, general counsel for the Federal Law Enforcement Officials Association, confirmed Thursday to the Associated Press that he is representing the two supervisors, Greg Stokes and David Chaney, but said he could not discuss details of the investigation.

Chaney, who protected former Republican vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin while working on her security detail during the 2008 campaign, once once joked on his Facebook page that he was "really checking her out."

Chaney made the comment on a photo of Palin that showed him standing in the background that was posted on his Facebook page in January 2009.

Details of the photo comments were first reported by The Washington Post. Speaking to Fox News, Palin said the scandal is "a symptom of government run amok."

"Well, check this out, buddy — you're fired!" Palin said.

Eleven agents and at least 10 military servicemembers — all part of an advance team that traveled to Colombia ahead of President Obama's visit last weekend for the Summit of the Americas— allegedly brought as many as 21 prostitutes to a hotel in Cartagena.

Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif., chairman of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, and Rep. Elijah Cummings, D-Md., have called on Sullivan to give lawmakers summaries of past misconduct by Secret Service officials during overseas trips over the past five years and to answer what lapses in agency policy may have contributed to the incident.

The two lawmakers also have asked the director for the disciplinary history of the officials involved in the incident and whether the Secret Service has been able to determine whether all of the women involved in the incident are at least 18.