Ruling Expands Rights of Accused in Plea Bargains

I think the real problem is that "plea bargains" have replaced "jury trials".If you are innocent and refuse to accept a "plea bargain", and are found guilty you will receive a draconian sentence because you demanded a trail.

In those cases innocent people frequently get screwed for demanding trials.

My view is that you have about as much chance of getting a fair trial as you do going to Las Vegas and winning a huge jackpot. Sure sometimes it happens, but most of the time you lose and get screwed.

The problem isn't fixing the "plea bargain" system, it should be getting rid of the "plea bargain" system.

Justices’ Ruling Expands Rights of Accused in Plea Bargains

By ADAM LIPTAK

Published: March 21, 2012

WASHINGTON — Criminal defendants have a constitutional right to effective lawyers during plea negotiations, the Supreme Court ruled on Wednesday in a pair of 5-to-4 decisions that vastly expanded judges’ supervision of the criminal justice system.

The decisions mean that what used to be informal and unregulated deal making is now subject to new constraints when bad legal advice leads defendants to reject favorable plea offers.

“Criminal justice today is for the most part a system of pleas, not a system of trials,” Justice Anthony M. Kennedy wrote for the majority. “The right to adequate assistance of counsel cannot be defined or enforced without taking account of the central role plea bargaining takes in securing convictions and determining sentences.”

Justice Kennedy, who more often joins the court’s conservative wing in ideologically divided cases, was in this case in a coalition with the court’s four more liberal members. That alignment has sometimes arisen in recent years in cases that seemed to offend Justice Kennedy’s sense of fair play.

The consequences of the two decisions are hard to predict because, as Justice Antonin Scalia said in a pair of dissents he summarized from the bench, “the court leaves all of this to be worked out in further litigation, which you can be sure there will be plenty of.”

Claims of ineffective assistance at trial are commonplace even though trials take place under a judge’s watchful eye. Challenges to plea agreements based on misconduct by defense lawyers will presumably be common as well, given how many more convictions follow guilty pleas and the fluid nature of plea negotiations.

Justice Scalia wrote that expanding constitutional protections to that realm “opens a whole new boutique of constitutional jurisprudence,” calling it “plea-bargaining law.”

Scholars agreed about its significance.

“The Supreme Court’s decision in these two cases constitute the single greatest revolution in the criminal justice process since Gideon v. Wainwright provided indigents the right to counsel,” said Wesley M. Oliver, a law professor at Widener University, referring to the landmark 1963 decision.

In the context of trials, the Supreme Court has long established that defendants were entitled to new trials if they could show that incompetent work by their lawyers probably affected the outcome. The Supreme Court has also required lawyers to offer competent advice in urging defendants to give up their right to a trial by accepting a guilty plea. Those cases hinged on the right to a fair trial guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment.

The cases decided Wednesday answered a harder question: What is to be done in cases in which a lawyer’s incompetence caused the client to reject a favorable plea bargain?

Justice Kennedy, joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen G. Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, acknowledged that allowing the possibility of do-overs in cases involving foregone pleas followed by convictions presented all sorts of knotty problems. But he said the realities of American criminal justice required to the court to take action.

Some 97 percent of convictions in federal courts were the result of guilty pleas. In 2006, the last year for which data was available, the corresponding percentage in state courts was 94.

“In today’s criminal justice system,” Justice Kennedy wrote, “the negotiation of a plea bargain, rather than the unfolding of a trial, is almost always the critical point for a defendant.”

Quoting from law review articles, Justice Kennedy wrote that plea bargaining “is not some adjunct to the criminal justice system; it is the criminal justice system.” He added that “longer sentences exist on the books largely for bargaining purposes.”

One of the cases, Missouri v. Frye, No. 10-444, involved Galin E. Frye, who was charged with driving without a license in 2007. A prosecutor offered to let him plead guilty in exchange for a 90-day sentence.

But Mr. Frye’s lawyer at the time, Michael Coles, failed to tell his client of the offer. After it expired, Mr. Frye pleaded guilty without a plea bargain, and a judge sentenced him to three years.

A state appeals court reversed his conviction but said it did not have the power to order the state to reduce the charges against him. That left Mr. Frye roughly where he started, with the options of going to trial or pleading guilty without the benefit of a plea deal.

Justice Kennedy wrote that Mr. Frye should have been allowed to try to prove that he would have accepted the original offer. But that was only the beginning of what Mr. Frye would have to show to get relief. He would also have to demonstrate, Justice Kennedy wrote, that prosecutors would not have later withdrawn the offer had he accepted it, as they were allowed to do under state law. Finally, Justice Kennedy went on, Mr. Frye would have to show that the court would have accepted the agreement.

There was reason for doubt that Mr. Frye could prove that prosecutors and the court would have ended up going along with the original 90-day offer, as Mr. Frye was again arrested for driving without a license before the original plea agreement would have become final.

Justice Scalia, in a dissent joined by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr., called all of this “a process of retrospective crystal-ball gazing posing as legal analysis.”

The second case, Lafler v. Cooper, No. 10-209, concerned Anthony Cooper, who shot a woman in Detroit in 2003 and then received bad legal advice. Because all four of his bullets had struck the victim below her waist, his lawyer incorrectly said, Mr. Cooper could not be convicted of assault with intent to murder.

Based on that advice, Mr. Cooper rejected a plea bargain that called for a sentence of four to seven years. He was convicted, and is serving 15 to 30 years.

Justice Kennedy rejected the argument that a fair trial was all Mr. Cooper was entitled to.

“The favorable sentence that eluded the defendant in the criminal proceeding appears to be the sentence he or others in his position would have received in the ordinary course, absent the failings of counsel,” he wrote.

A federal judge in Mr. Cooper’s case tried to roll back the clock, requiring officials to provide him with the initial deal or release him. Justice Kennedy said the correct remedy was to require the plea deal to be re-offered and then to allow the trial court to resentence Mr. Cooper as it sees fit if he accepts it.

Justice Scalia, here joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Thomas, said this was “a remedy unheard of in American jurisprudence.”

“I suspect that the court’s squeamishness in fashioning a remedy, and the incoherence of what it comes up with, is attributable to its realization, deep down, that there is no real constitutional violation here anyway,” Justice Scalia wrote. “The defendant has been fairly tried, lawfully convicted and properly sentenced, and any ‘remedy’ provided for this will do nothing but undo the just results of a fair adversarial process.”

Stephanos Bibas, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania and an authority on plea bargaining, said the decisions were a great step forward. But he acknowledged that it may give rise to gamesmanship.

“It is going to be tricky,” he said, “and there are going to be a lot of defendants who say after they’re convicted that they really would have taken the plea.”

Justice Kennedy suggested several “measures to help ensure against late, frivolous or fabricated claims.” Among them were requiring that plea offers be in writing or made in open court.

This article talks about how the Supreme Court case will effect plea bargains in Arizona.

Computer chips keep track of students in Brazil

Mar. 22, 2012 12:15 PM

Associated Press

SAO PAULO -- Grade-school students in a northeastern Brazilian city are using uniforms embedded with computer chips that alert parents if they're cutting classes, the city's education secretary said Thursday.

Twenty thousand students in 25 of the of Vitoria da Conquista's 213 public schools started using T-shirts with chips earlier this week, secretary Coriolano Moraes said by telephone.

By 2013, all of the city's 43,000 public school students -- aged 4 to 14 -- will be using the chip-embedded T-shirts, he added.

The "intelligent uniforms" tell parents when their children enter the school building by sending a text message to their cell phones. Parents are also alerted if kids don't show up 20 minutes after classes begin with the following message: "Your child has still not arrived at school."

"We noticed that many parents would bring their children to school but would not see if they actually entered the building because they always left in a hurry to get to work on time," Moraes said in a telephone interview. "They would always be surprised when told of the number times their children skipped class.

After a student skips classes three times parents will be asked to explain the absences. If they fail to do so the school may notify authorities, Moares said.

The city government invested $670,000 to design, test and make the microchipped T-shirts, he said.

The chips are placed underneath each school's coat-of-arms or on one of the sleeves below a phrase that says: "Education does not transform the world. Education changes people and people transform the world."

The T-shirts, can be washed and ironed without damaging the chips, Moraes said adding that the chips have a "security system that makes tampering virtually impossible."

Moraes said that Vitoria da Conquista is the first city in Brazil "and maybe in the world" to use this system.

"I believe we may be setting a trend because we have received many requests from all over Brazil for information on how our system works," he said.

U.S. to keep data on citizens with no terror ties

by Eileen Sullivan - Mar. 22, 2012 08:53 PM

Associated Press

WASHINGTON - The U.S. intelligence community will be able to store information about Americans with no ties to terrorism for up to five years under new Obama administration guidelines.

Until now, the National Counterterrorism Center had to destroy immediately information about Americans that already was stored in other government databases when there were no clear ties to terrorism.

Giving the NCTC expanded record-retention authority had been urged by members of Congress, who said the intelligence community did not connect strands of intelligence held by multiple agencies leading up to a failed bombing attempt on a U.S.-bound airliner on Christmas 2009.

"Following the failed terrorist attack in December 2009, representatives of the counterterrorism community concluded it is vital for NCTC to be provided with a variety of datasets from various agencies that contain terrorism information," Director of National Intelligence James Clapper said in a statement late Thursday. "The ability to search against these datasets for up to five years on a continuing basis as these updated guidelines permit will enable NCTC to accomplish its mission more practically and effectively."

The new rules replace guidelines issued in 2008 and have privacy advocates concerned about the potential for data-mining information on innocent Americans.

"It is a vast expansion of the government's surveillance authority," Marc Rotenberg, executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, said of the five-year retention period.

The government put in strong safeguards at the NCTC for the data that would be collected on U.S. citizens for intelligence purposes, Rotenberg said. These new guidelines undercut the Federal Privacy Act, he said.

"The fact that this data can be retained for five years on U.S. citizens for whom there's no evidence of criminal conduct is very disturbing," Rotenberg said.

"Total Information Awareness appears to be reconstructing itself," he said, referring to the Defense Department's data-mining research program that began after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks but was stopped in 2003 because of privacy concerns.

The Washington Post first reported the new rules Thursday.

The Obama administration said the new rules come with strong safeguards for privacy and civil liberties, as well.

The NCTC was created after the Sept. 11 attacks to analyze and integrate intelligence regarding terrorism.

1984 is here, even if it is a few years late!

1984 is here, even if it is a few years late!

Uncle Sam is spying on you

Source

New counterterrorism guidelines

Source

New counterterrorism guidelines permit data on U.S. citizens to be held longer

By Sari Horwitz and Ellen Nakashima, Published: March 22

The Obama administration has approved guidelines that allow counterterrorism officials to lengthen the period of time they retain information about U.S. residents, even if they have no known connection to terrorism.

The changes allow the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), the intelligence community’s clearinghouse for terrorism data, to keep information for up to five years. Previously, the center was required to promptly destroy — generally within 180 days — any information about U.S. citizens or residents unless a connection to terrorism was evident.

The new guidelines, which were approved Thursday by Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr., have been in the works for more than a year, officials said.

The guidelines have prompted concern from civil liberties advocates.

Those advocates have repeatedly clashed with the administration over a host of national security issues, including its military detention without trial of individuals in Afghanistan and at Guantanamo Bay, its authorization of the killing of U.S.-born cleric Anwar al-Awlaki in a drone strike in Yemen, and its prosecution of an unprecedented number of suspects in the leaking of classified information.

Officials said the guidelines are aimed at making sure relevant terrorism information is readily accessible to analysts, while guarding against privacy intrusions. Among other provisions, agencies that share data with the NCTC may negotiate to have the data held for shorter periods. That information can pertain to noncitizens as well as to “U.S. persons” — American citizens and legal permanent residents.

The director of national intelligence, James R. Clapper Jr., has signed off on the changes.

“A number of different agencies looked at these to try to make sure that everyone was comfortable that we had the correct balance here between the information-sharing that was needed to protect the country and protections for people’s privacy and civil liberties,” said Robert S. Litt, the general counsel in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, which oversees the NCTC.

Although the guidelines cover a variety of issues, the retention of data was the primary focus of negotiations with federal agencies. Those agencies provide the center with information such as visa and travel records and data from the FBI.

The old guidelines were“very limiting,” Litt said. “On Day One, you may look at something and think that it has nothing to do with terrorism. Then six months later, all of a sudden, it becomes relevant.”

Since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the government has taken steps to break down barriers in information-sharing between law enforcement and the intelligence community, but policy hurdles remain.

The NCTC, created by the 2004 Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act, collects information from numerous agencies and maintains access to about 30 data sets across the government. But privacy safeguards differ from agency to agency, in some cases hindering timely and effective analysis, senior intelligence officials said.

“We have been pushing for this because NCTC’s success depends on having full access to all of the data that the U.S. has lawfully collected,” said Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Mich.), chairman of the House intelligence committee. “I don’t want to leave any possibility of another catastrophic attack that was not prevented because an important piece of information was hidden in some filing cabinet.”

The shootings at Fort Hood, Tex., and the attempted downing of a Detroit-bound airliner on Christmas Day 2009 gave new impetus to efforts to aggregate and analyze terrorism-related data more effectively.

In the case of Fort Hood, Maj. Nidal M. Hasan had had contact with Awlaki but that information had not been shared across the government. The name of Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the suspect in the 2009 airliner plot, had been placed in a master list housed at the NCTC but not on a terrorist watch list that would have prevented him from boarding the plane.

Officials said the privacy safeguards in the new guidelines include limits on the NCTC’s ability to redistribute information to other agencies.

“Within the intelligence community, there’s one set of controls for terrorism purposes, a stricter set of controls for non-terrorism purposes, and an even stricter set of controls for dissemination outside the intelligence community,” an official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity. An entire database cannot be shared; only specific information within that data set can be shared, and it must be with the approval of the agency that provided the data, the official said.

Privacy advocates said they were concerned by the new guidelines, despite the safeguards.

The purpose of the safeguards is to ensure that the “robust tools that we give the military and intelligence community to protect Americans from foreign threats aren’t directed back against Americans,” said the American Civil Liberties Union’s national security policy counsel, Michael German. “Watering down those rules raises significant concerns that U.S. persons are being targeted or swept up in these collection programs and can be harmed by continuing investigations for as long as these agencies hold the data.”

Other homeland security experts said the guidelines give officials more flexibility without compromising individual privacy.

“Five years is a reasonable time frame,” said Paul Rosenzweig, a former senior Department of Homeland Security policy official. “I certainly think 180 days was way too short. That’s just not a realistic understanding” of how long it takes analysts to search large data sets for relevant information, he said.

Drug tests to get unemployment???

First of all "unemployment" is NOT a government welfare program people get for "free". Employees and employers pay a tax on the wages employees earn and that tax is used to fund the "unemployment" program.I find it outrageous that the government requires employees and employers to pay this "unemployment insurance tax", and then the government wants to skip out on making the insurance payments if an employee uses drugs.

Second I find it outrageous that our government masters are forcing people to submit to a "search" of their body without having the required "probable cause", which sounds like it violated the 4th Amendment against searches.

Drug test for unemployed advances in Arizona House

Screening would be required to get benefits

by Mary Jo Pitzl - Mar. 22, 2012 10:55 PM

The Republic | azcentral.com

If you're out of work, Arizona lawmakers want to make you take a drug test before you get an unemployment check.

And the unemployed worker would have to pay for it.

Arizona state Sen. Steve Smith, R-Maricopa, said he wrote Senate Bill 1495 to ensure people who get unemployment benefits are deserving. He doesn't consider anyone who uses drugs fit for assistance.

"If you are so fortunate to live in a nation to get an unemployment check ... when you're down on your luck, the very least you should be able to do is prove you're of sound mind and body to earn -- earn -- that benefit," Smith told members of the House Appropriations Committee on Thursday.

The committee passed the measure Thursday on a 7-6 vote over the protests of the business community and concerns about conflicts with federal law.

It will now be considered by the full House of Representatives. While its prospects there are shaky, it is the latest in a trend of attempts to erect hurdles for people who rely on government help.

In the past two years, 20 states have considered laws requiring drug tests for unemployment beneficiaries, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Indiana is the only state where a bill passed.

Last year, the Arizona Legislature considered a bill to drug-test anyone on food stamps. The bill eventually died.

This year's bill would require the state Department of Economic Security to set up a drug-testing program.

Any first-time applicant for unemployment benefits who gets a positive drug-test result would have to wait 30 days to retest and could not get benefits in the meantime.

Those already receiving benefits would face random tests, and anyone who failed would lose his or her current month's pay and be required to take monthly tests for the next six months.

The bill would require unemployed workers to pay for their tests, which run $35 to $45 at one Valley lab. However, Smith said, drug tests can be had for $20.

As of mid-March, 81,999 Arizonans were receiving unemployment checks of $240 a week, according to the DES. The money comes from a tax paid by employers. In exchange for participating in the program, employers receive a federal tax break.

Arizona provides 26 weeks of unemployment benefits, after which the federal government provides additional weeks.

"We've got to get our fiscal house in order," Smith said, adding that the bill is needed to end "waste, fraud and abuse" in state and federal programs.

Smith's arguments didn't go over well with committee members. Even those who voted for the bill indicated they might be a "no" if the bill isn't further changed.

"We're chasing the wrong federal program," said Rep. Vic Williams, R-Tucson. "This is not a welfare program."

The assumption that people who file unemployment claims are drug abusers is "wrong-minded," Williams said. The recession has swelled the number of people on unemployment, he said, not sloth or drug abuse.

"We are going down the wrong road in Arizona when so-called conservative programs go after the business community," he said.

Representatives of the Arizona and Greater Phoenix chambers of commerce and numerous other businesses opposed the bill.

Marc Osborn, representing the Arizona Chamber of Commerce & Industry, said the bill could imperil the federal tax break for employers. He said the U.S. Department of Labor has noted several areas where SB 1495 conflicts with federal law.

In a letter to the state DES, which administers unemployment, Gay Gilbert, administrator of the federal Office of Unemployment Insurance, said it is unconstitutional to require a drug test as a condition for unemployment benefits.

Gilbert added that federal law also requires anyone denied unemployment benefits to appeal, which is not included in the Arizona bill.

The requirement for the person to pay for drug-testing costs also is troublesome, Gilbert wrote, because it could discourage people from applying for benefits in a timely manner -- which could run afoul of a requirement to provide benefits quickly.

Smith called the concerns a "bluff," saying he doubts the federal government would enforce restrictions by removing the tax break.

However state Rep. Nancy McLain, R-Bullhead City, said she doesn't want to take that gamble. It's employers who would suffer, said McLain, who owns a small business.

Appropriations Chairman John Kavanagh, R-Fountain Hills, proposed an amendment to authorize a drug-testing program that fits with federal law. It passed.

The federal law, changed last month by Congress, lets states drug-test unemployment applicants in two cases: If the individual was fired for drug abuse, or if the person is seeking a job that requires drug testing. People receiving unemployment benefits are expected to search for jobs.

Rep. Justin Olson, R-Mesa, said the fix is simple: Amend the bill to require drug testing in those two circumstances. That way, Arizona employers would still comply with the federal unemployment program.

Smith indicated he might not accept those limitations. He's interested in a wider test of unemployment recipients. In Indiana, the year-old drug-testing law allows, but does not require, employers to report people who fail a pre-employment drug test. If the state confirms those results, the individual can lose unemployment benefits, said Valerie Kroeger, a state spokeswoman. She did not have statistics on program results.

Kroeger said another Indiana program has found little problem with drug abuse among the unemployed. State policy requires people who enroll in a job-training program to take drug tests.

Of the 2,500 people who have enrolled in the program, 97.5 percent tested clean.

Russell Pearce a soldier in Christian ‘war on women’

SourceLetter: Pearce a soldier in ‘war on women’

Posted: Thursday, March 22, 2012 3:41 pm

Letter to the Editor

Russell Pearce is back saying that he is “100 percent pro-life” and “100 percent for freedom”. It is unfortunate that Pearce does not recognize that by denying women the right to make decisions concerning their bodies, there is no freedom. Pearce is just one more foot soldier in the Republican Party’s War on Women.

Tom Kenney

Gilbert

Russell Pearce a soldier in Republican ‘war on women’

SourceLetter: Pearce a soldier in ‘war on women’

Posted: Thursday, March 22, 2012 3:41 pm

Letter to the Editor

Russell Pearce is back saying that he is “100 percent pro-life” and “100 percent for freedom”. It is unfortunate that Pearce does not recognize that by denying women the right to make decisions concerning their bodies, there is no freedom. Pearce is just one more foot soldier in the Republican Party’s War on Women.

Tom Kenney

Gilbert

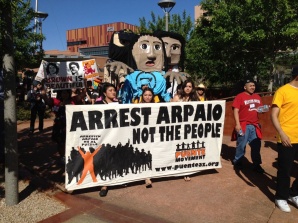

ASU Students protest Sheriff Joe Arpaio

Students stage another protest of Arpaio, immigration policies

Mar. 23, 2012 05:20 PM

The Republic | azcentral.com

Scores of mostly college and high school students marched in downtown Phoenix Friday afternoon to protest Sheriff Joe Arpaio and his continued crackdown on illegal immigrants.

The protesters gathered at a park near Central Avenue and Fillmore Street and began marching about 3:30 p.m. toward a downtown building where Arpaio and his office leases space. The marchers were planning to go from there to the state Capitol by 17th Avenue and Jefferson Street.

It was the second time in three days that young people have staged a protest of the Maricopa County Sheriff -- in the first instance, the event was staged by Dream Activist, an online organization that's encouraging young undocumented immigrants to "come out of the shadows" by getting arrested.

Friday's protest was coordinated by the Arizona State University chapter of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA), a student organization that promotes political participation for social change. About 600 students from across the nation are in town for the 2012 National MEChA Conference. Jose Rios, an ASU student and one of the conference's planners, said the event also got assistance from PUENTE, a group that seeks to promote human rights.

In the earlier protest Tuesday, just outside Trevor Browne High School in northwest Phoenix, six people, including two juveniles, were arrested by Phoenix police on suspicion of disrupting a thoroughfare and disorderly conduct. That event drew about 150 people and led to a shutdown of a portion of 75th Avenue.

Dream Activist has organized acts of civil disobedience in more than six cities in recent years, including the one in Phoenix, that have resulted in the arrests of more than 60 young undocumented immigrants, many of them students or recent graduates, a group spokesman said earlier this week.

At Tuesday's march, protesters repeatedly chanted "undocumented and unafraid" during the nearly 4-hour protest.

Some held signs reading "Support the DREAM Act!" and "We will no longer remain in the shadows."

On the other hand if you are creating a jobs program for overpaid Secret Service thugs, I guess you want to arrest people for any trivial thing you can find.

Obama comment made during Santorum visit probed

by Sarah Eddington - Mar. 23, 2012 04:59 PM

MONROE, La. -- A comment made by a spectator during Republican presidential candidate Rick Santorum's visit to West Monroe has led to a Secret Service investigation.

Santorum was at the Ouachita Parish Sheriff's Office Rifle Range on Friday morning as part of his campaign through Louisiana before Saturday's Republican presidential primary.

While Santorum was firing off some rounds from a gun at a paper target before delivering his campaign speech , an unidentified woman in the crowd shouted: "Pretend it's Obama."

Santorum, who was wearing protective shooting ear muffs at the time, later told reporters he didn't hear the woman's "absurd" remark.

"It's a very terrible and horrible remark, and I'm glad I didn't hear it," he said.

A representative from the Secret Service confirmed the incident and the fact that the agency is looking into the matter, but couldn't provide further details.

"We are conducting the appropriate investigative steps," said George Ogilvie, public affairs officer for the Secret Service.

Officers Get Union Checks After Shootings

By Jeff Proctor / Journal Staff Writer on Fri, Mar 23, 2012

Twenty Albuquerque police officers involved in shootings in 2010 and 2011 received payments from the police union of either $300 or $500, the Journal has learned.

A written statement from Albuquerque Police Officers Association President Joey Sigala and Vice President Felipe Garcia said the payments are to cover some expenses for officers who have been involved in “critical incidents” and their families “to find a place to have some privacy and time to decompress outside the Albuquerque area.”

“We do not determine where they go or for how long, we simply give them some means of obtaining this critical time to gather their thoughts and emotions after a stressful incident,” the statement said.

Top city officials said they had been unaware of the practice and didn’t want to comment until they talked to union officials; the father of one man shot by a police officer blasted the practice as “bounty.”

The APOA statement – issued in response to an inquiry from the Journal based on a document showing the payments in 2010 and 2011 – said officers typically received the payments within the first couple of days after the shootings.

A photo and Albuquerque Police Department information about Gary E. Atencio was on a screen during a news conference Thursday identifying Atencio as the man who was shot by police after a high-speed chase.

Sigala and Garcia declined to be interviewed, and their statement did not say whether union officials offer the payments or whether officers have to ask for them.

Sigala did not respond to a question asking whether officers involved in three shootings this year had, or would, receive the payments.

The statement seemed to indicate the practice has gone on “for years,” but did not say whether it is an official APOA policy or exactly how long it has been done.

Police Chief Ray Schultz said he was unaware of the practice.

In fact, Schultz said through a spokesman he was not aware of such a practice when he was a member of the union, and he did not receive any money from the APOA after he was involved in a shooting after an armed robbery in 1986.

Schultz declined through a spokesman to comment on the practice, saying he wanted to speak with Sigala first.

The city provides counselling for officers involved in shootings and other critical incidents.

Albuquerque Chief Administrative Officer Rob Perry said the union is entitled to do as it wishes with its money and declined further comment until he learned more about the payments.

Family members of the 20 men shot by APD officers in 2010 and 2011 blasted the payouts, calling them an apparent “bounty.”

“It’s unbelievable to find this out,” said Mike Gomez, whose son, Alan, was fatally shot by APD officer Sean Wallace last year. “This just sounds like a reward system, a bounty. If it’s in these cops’ minds that they’re going to get rewarded if they shoot someone, even if they don’t kill them, that’s just not good.”

Wallace was among those who received $500 in 2011. He also received $500 after a non-fatal shooting in 2010.

The statement from Sigala and Garcia said the payments are intended as support for officers.

“We also believe that any claim or assertion that these were somehow cash payments for the officer merely ‘shooting someone’ are absolutely ridiculous and false,” the statement says. “We hold onto the honor and dignity of our profession and would never engage in such callous and hurtful behavior.”

In all, 23 APD officers shot people during 20 incidents last year and the year before. Fifteen of those shootings were fatal.

Internal union financial documents obtained by the Journal show 20 of the officers received union payments. Of those, 16 received $500, two were paid $300, one received $800 and a payment of $1,000 went to one officer.

Also, $500 in union funds went to an officer who did not fire any shots but was involved in an incident that ended when another officer fatally shot a man.

The documents show more than $10,000 went to officers involved in shootings.

The statement from Sigala and Garcia said the union only makes “partial payments of up to $500 to help cover the costs” of out-of-town stays.

“In many cases, it has been less,” the statement says. “There were no disbursements over $500, and any costs … which are over $500 are for other union-related matters.”

The 20 officer-involved shootings in 2010 and 2011 have drawn an angry response, with critics flooding City Council meetings, holding protests and demanding Schultz’s resignation and more accountability from APD.

Critics have pointed out that the majority of those shot were Hispanic men in their 20s and 30s.

All the shootings that have worked through the review process have been ruled justified through APD’s internal affairs process and by grand jury review after presentation by the District Attorney’s Office.

The U.S. Department of Justice is considering whether to conduct a full-scale investigation to determine whether APD has a pattern or practice of violating civil rights.

Financial review

The documents obtained by the Journal were prepared by union Treasurer Matt Fisher earlier this month after members demanded to see a breakdown of how APOA money was being spent.

The demands came after Fred Mowrer, the union’s lawyer, sent an email to board members saying $259,000 had been spent on salaries and “union work” during the past two years – at a time when the APOA was supposed to be pinching pennies in anticipation of a court battle against the Berry administration over police contracts.

The union sued Mayor Richard Berry in 2010, contending he illegally backed out of an agreement signed by the previous administration to raise APD pay. The city won the first round, but the union appealed to the state Court of Appeals, which hasn’t yet ruled.

APOA members voted last week to hire an outside firm to audit the union’s finances for the past two years and to require more financial accountability going forward. Members will also consider next month whether the president’s and vice president’s union salaries should be cut.

The moves followed revelations at a March 15 APOA meeting from Sigala that he and Vice President Felipe Garcia have paid themselves more in salary from union dues than they previously acknowledged publicly, and that Sigala’s wife was paid about $6,000 for working on “special projects” and filling in as a temporary administrative secretary.

— This article appeared on page A1 of the Albuquerque Journal

Berry: Shooting Payouts Must End

By Jeff Proctor / Journal Staff Writer on Sat, Mar 24, 2012

A defiant police union President Joey Sigala said late Friday that the union will continue to financially support officers who have been involved in shootings, despite calls earlier in the day from the mayor and police chief for the practice to stop.

Mayor Richard Berry said in a statement that he was “shocked” to learn of the practice and said it “needs to end now,” while Police Chief Ray Schultz called the payments “troubling.”

A Journal story published Friday revealed that the union had paid more than $10,000 to officers involved in shootings, dating to the start of 2010.

In all, 23 APD officers shot people during 20 incidents last year and the year before. Fifteen of those shootings were fatal.

Internal union financial documents obtained by the Journal show that 20 of the officers received union payments. Of those, 16 received $500, two were paid $300, one received $800 and a payment of $1,000 went to one officer.

The documents did not indicate whether officers involved in three shootings this year also received checks, but APOA leaders on Thursday explained and defended the practice.

Outside an emergency meeting of the union board at Albuquerque Police Officers Association headquarters Downtown, Sigala said the union has made cash payments and supported in other ways officers involved in shootings and other “critical incidents” for more than 20 years.

Sigala said he did not know whether the payments were made in nearly every shooting case — as they have been during his tenure as president — under previous union administrations.

But he said the practice has been well-known among rank-and-file police officers, as well as the department’s “upper administration.”

On Thursday, Schultz said he was not aware of the practice, adding that it was not in place when he was a member of the union and that he did not receive any money from the APOA when he was involved in a shooting after an armed robbery in 1986.

On Friday, he issued a statement through a spokeswoman.

“What we have learned about this practice thus far is troubling,” the statement said. “We support our officers when they are placed in these critical incidents. However, we recognize the union is further putting these officers in an untenable situation that we don’t agree with.”

Asked Friday whether Schultz specifically knew about the payments, Sigala said: “The chief has been the chief for a long time.”

Sigala said he and union Vice President Felipe Garcia have been making decisions on whether officers involved in shootings should get financial support. Going forward, he said, the entire 20-member union board will decide on a case-by-case basis which officers will get money.

The payments are limited to $500, Sigala said, adding that larger amounts shown in the documents mean officers also have done other union work.

Berry criticized the payments.

“I cannot stand aside and condone this practice — it needs to end now,” the mayor said in a prepared statement. “We all support our fine officers, but I have directed Chief Schultz to work with the union to ensure this practice no longer continues.”

The mayor declined through a spokeswoman to elaborate.

Sigala said Berry has “no idea what it’s like” to be a police officer faced with a decision about using deadly force and should not have condemned the payments out of hand — especially without speaking with union leaders.

Sigala and Garcia said in a statement Thursday that the payments were to cover some expenses for officers who have been involved in “critical incidents” and their families “to find a place to have some privacy and time to decompress outside the Albuquerque area.”

The father of one of the men fatally shot by an APD officer in the past few years described the payments as “bounty.”

The city provides counseling for officers involved in shootings and other critical incidents, and all officers are placed on leave with pay after a shooting.

City leaders “understand that supporting officers is important,” Sigala said. “So do we.”

Money questions

The documents obtained by the Journal were prepared by union Treasurer Matt Fisher earlier this month after members demanded to see a breakdown of how APOA money was being spent.

The demands came after Fred Mowrer, the union’s lawyer, sent an email to board members saying $259,000 had been spent on salaries and “union work” during the past two years — at a time when the APOA was supposed to be marshaling its resources in anticipation of a court battle against the Berry administration over police contracts.

The union sued Berry in 2010, contending he illegally backed out of an agreement signed by the previous administration to raise APD pay. The city won the first round, but the union appealed to the state Court of Appeals, which hasn’t yet ruled.

APOA members voted last week to hire an outside firm to audit the union’s finances for the past two years and to require more financial accountability. Members will also consider next month whether the president’s and vice president’s union salaries should be cut.

The moves followed revelations from Sigala at a March 15 APOA meeting that he and Garcia have paid themselves more in salary from union dues than they previously acknowledged publicly, and that Sigala’s wife was paid about $6,000 for working on special projects and filling in as a temporary secretary.

One union member confirmed that Sigala and Garcia said during the meeting that they had paid themselves about $36,000 and $28,000, respectively, in salaries funded by dues last year.

Sigala last month told the Journal he receives about $26,000 annually for union work — on top of his $52,374 APD salary — and Garcia makes $19,500 a year plus his city salary, which is the same as Sigala’s.

— This article appeared on page A1 of the

Albuquerque Journal

BREAKING: Mayor, APD Chief Call For Halt To Shooter Payouts

By Jeff Proctor / Journal Staff Writer on Fri, Mar 23, 2012

Mayor Richard Berry and APD Chief Ray Schultz have issued statements calling for a halt to the police union’s practice of issuing $500 checks to officers involved in shootings.

Here’s the mayor’s statement:

“The administration has nothing to do with how the union conducts their business, but I was shocked yesterday when made aware of this practice. I cannot stand aside and condone this practice– it needs to end now. We all support our fine officers, but I have directed Chief Shultz to work with the union to ensure this practice no longer continues.”

“What we have learned about this practice thus far is troubling. We support our officers when they are placed in these critical incidents. However, we recognize the union is further putting these officers in an untenable situation that we don’t agree with. After discussions with Chief Schultz this morning, the union has agreed to hold an emergency board meeting to discuss suspending the practice.”

The statements are in response to this morning’s Journal story, which you can read here.

Pick up a copy of tomorrow’s paper for continuing coverage.

New Mexico police in shootings get cash

Mar. 23, 2012 10:46 PM

Associated Press

ALBUQUERQUE - Albuquerque police officers involved in a rash of fatal shootings over the past two years were paid up to $500 under a union program that some have likened to a bounty system in a department with a culture that critics have long contended promotes brutality.

Mayor Richard Berry called Friday for an immediate halt to the practice, which was first reported in the Albuquerque Journal during a week in which Albuquerque police shot and killed two men.

Since 2010, Albuquerque police have shot 23 people, 18 fatally.

"The administration has nothing to do with how the union conducts their business," Berry said in a statement, "but I was shocked yesterday when made aware of this practice. I cannot stand aside and condone this practice. It needs to end now."

Although the union said the payments were intended to help the officers decompress from a stressful situation, one victim's father and a criminologist said it sounded more like a reward program.

"I think it might not be a bounty that they want it for," said Mike Gomez, the father of an unarmed man killed by police last year, "but in these police guys' minds, they know they are going to get that money. So when they get in a situation, it's who's going to get him first? Who's going to shoot him first?"

Maria Haberfeld, chair of the Department of Law & Police Science at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, said she found the program disturbing.

"I'm not a psychologist. I'm a criminologist. But if you give somebody a monetary incentive to do their job, usually people are tempted by the monetary incentive," she said.

Other law-enforcement officials called speculation of a bounty system ridiculous.

"Frankly, it's insulting and very insensitive that somebody would believe that a police officer would factor in a payment for such a difficult decision," said Joe Clure, president of the Phoenix Law Enforcement Association.

Officer in Bell Killing Is Fired; 3 Others to Be Forced Out

By MATT FLEGENHEIMER and AL BAKER

Published: March 23, 2012

The New York City police detective who fired the first shots in the 50-bullet barrage that killed Sean Bell in 2006 has been fired, and three others involved in the shooting are being forced to resign, law enforcement officials said on Friday.

The decision came after a Police Department administrative trial in the fall found that the detective, Gescard F. Isnora, had acted improperly in the shooting that killed Mr. Bell on what was supposed to have been his wedding day and that he should be fired.

“There was nothing in the record to warrant overturning the decision of the department’s trial judge,” Deputy Commissioner Paul J. Browne said on Friday night.

Law enforcement officials said word of Police Commissioner Raymond W. Kelly’s decision came late Friday. Detective Isnora, an 11-year veteran, will not collect a pension, one official said. “He loses everything,” the official said.

Three other officers — Detectives Marc Cooper and Michael Oliver, who fired shots at Mr. Bell; and Lt. Gary Napoli, a supervisor who was at the scene but did not fire any shots — are being forced to resign.

Detectives Isnora, Cooper and Oliver were acquitted in a criminal trial in 2008 on charges of manslaughter, assault and reckless endangerment.

A fourth officer who fired his gun during the episode, Detective Paul Headley, has already left the department, and a fifth, Officer Michael Carey, was exonerated in the department’s administrative trial.

Detective Cooper and Lieutenant Napoli, who worked in the department for more than 20 years, will receive their pensions, a law enforcement official said. Detective Oliver, who has served for 18 years, may collect on a pension on the 20th anniversary of his start date, the official said.

The shooting of Mr. Bell, 23, who did not have a gun, occurred in the early morning on Nov. 25, 2006, as Mr. Bell and two friends were leaving a strip club in Jamaica, Queens, where they had been celebrating. The case drew widespread scrutiny of undercover police tactics.

Prosecutors questioned the judgment of the shooters, with one arguing in the department’s trial that Detective Isnora overreacted, leading to “contagious firing” from those who followed his cue.

Detective Isnora testified that he thought Mr. Bell and a friend were about to take part in a drive-by shooting. He has said he believed, after overhearing a heated argument in front of the strip club, that the friend had a gun.

In July 2010, the city agreed to pay more than $7 million to settle a federal lawsuit filed by Mr. Bell’s family and two of his friends.

Sanford A. Rubenstein, a lawyer who has represented the Bell estate and the two men wounded along with Mr. Bell, said, regarding Detective Isnora, “The police commissioner followed the trial judge’s ruling, which was clearly appropriate based on the evidence.” Of the other disciplined officers, Mr. Rubenstein said, “I think the fact that they’re no longer on the police force is appropriate.”

Mr. Isnora’s lawyer, Philip E. Karasyk, said, “The commissioner’s decision to terminate Detective Isnora is extremely disheartening and callous and sends an uncaring message to the hard-working officers of the New York Police Department who put their lives on the line every day.”

Michael J. Palladino, the president of the Detectives’ Endowment Association, called Detective Isnora’s firing “disgraceful, excessive, and unprecedented.”

He continued: “Stripping a police officer of his livelihood and his opportunity for retirement is a punishment reserved for a cop who has turned to a life of crime and disgraces the shield. It is not for someone who has acted within the law and was justified in a court of law and exonerated by the U.S. Department of Justice.”

Many detectives were bracing for the decision after Deputy Commissioner Martin G. Karopkin, acting as the trial judge, recommended the punishment in November.

One law enforcement official said that, as the reality of the decisions sink in, they could have a drastic impact on how detectives view their work, particularly in the department’s undercover programs.

William K. Rashbaum contributed reporting.

Plea ruling to have little impact in Arizona

by Dennis Wagner - Mar. 23, 2012 11:12 PM

The Republic | azcentral.com

A U.S. Supreme Court decision this week that was widely described as a game-changer in the criminal-justice system will probably have little impact in Arizona, experts say, because state courts established a similar rule more than a decade ago.

On Wednesday, the nation's high court issued two findings that establish a defendant's constitutional right to effective legal counsel concerning plea bargains. The court was split 5-4 in both rulings, and Justice Antonin Scalia decried the majority opinion in dissent. He suggested that the court's verdict would open a floodgate of litigation from convicts arguing that they were mis-informed about plea deals.

Legal experts in Arizona generally disagreed, noting that the Court of Appeals here in 2000 reached a similar decision in a case known as State vs. Donald. Since then, Arizona judges have routinely conducted so-called Donald hearings before trial to ensure that defendants are adequately informed about plea offers.

In fact, the Supreme Court majority cited Arizona's practice as evidence that a defendant's right to competent representation can be protected without upending the justice system.

Robert McWhirter, training director with the Pima County Attorney's Office and a board member of Arizona Attorneys for Criminal Justice, a non-profit organization of defense lawyers, said the national ruling may have a "limited impact" as some prison inmates hear of the decision and try to challenge their convictions.

In the long run, however, McWhirter said the justice system will be improved. Other states will have to initiate procedures similar to the Donald hearings, and defense lawyers may have to explain plea offers in writing for their clients. Once reforms are in place, McWhirter said, he anticipates less litigation, not more.

"What the Donald hearings have done is save a huge amount of resources by preventing efforts for post-conviction relief," he said. "Sure, guys are going to jump up in their jail cells now and say, 'My attorney didn't tell me (about a plea offer).' But those cases will be weeded out pretty quickly, and it will pass."

McWhirter and Greg Parzych, another defense lawyer, said the significance of the Supreme Court ruling was overblown in some news reports, perhaps because of Scalia's vitriolic dissent.

Defendants who accept plea deals typically are found guilty on reduced charges and face less-severe penalties.

The Supreme Court decisions stem from cases in Missouri and Michigan. In the first, a drunken-driving suspect named Galin Edward Frye was not even told about the plea deal offered before his conviction. In the second, a shooting suspect named Anthony Cooper rejected an agreement after his lawyer incorrectly advised that conviction for attempted murder was impossible because the victim was wounded below the waist.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing the majority opinions, noted that more than 97 percent of all federal convictions result from negotiated pleas. Although defendants are not entitled to such deals, he said, the Sixth Amendment guarantees competent legal advice when they are offered.

That decision does not mean charges get dropped. Rather, cases must be returned to lower court for a finding as to whether the defendant is entitled to accept the earlier plea or, under some circumstances, a new offer from prosecutors.

The Arizona Court of Appeals case, although distinct in detail, seems to have presaged the Supreme Court decision.

Victor Gene Donald was charged with multiple armed robberies in 1993. His attorney allegedly failed to explain that, under a plea offered by prosecutors, he would serve "soft time" and get out of prison within four years. Donald went to trial and was convicted; he was sentenced to a full 10 years in prison.

Acting as his own attorney, Donald successfully appealed. Then-appellate Judges Noel Fidel and Thomas Kleinschmidt returned his case to the trial court based on the same legal reasoning that emerged from the Supreme Court this week.

A complete file was not immediately available, but online records from Maricopa County Superior Court and the Arizona Department of Corrections indicate Donald pleaded guilty in 2002, received an eight-year sentence and was released immediately due to time already served.

Former Maricopa County Attorney Rick Romley, who was in office at the time, applauded the Supreme Court decision. Noting that the vast majority of criminal cases are resolved early with plea deals, he said, "If you believe in our justice system and fundamental rights, it only flows to have competent counsel in the very beginning of the process."

Bill Montgomery, the current county attorney, agreed that the federal ruling will have a negligible impact on prosecutions in Arizona. However, he denounced a portion of the Supreme Court opinion that says some criminal statutes are adopted with excessive penalties so that prosecutors can pressure defendants into pleading guilty.

Montgomery described that section of the ruling as "crap" and "total, unmitigated BS," adding, "I think that's malpractice" by the nation's highest judges.

Arizona Attorney General Tom Horne disagreed with other Arizona lawyers, describing Wednesday's federal ruling as "troublesome" and "a big change."

Horne said "ineffective counsel" has always been defined as legal representation so incompetent that a defendant is deprived of the right to a fair trial with reliable results. Now, he said, criminal suspects can be convicted in fair trials yet have the guilty verdict overturned because they were misinformed about earlier plea deals.

"A lot of questions are being raised," Horne said. "I disagree with the ruling, but we're going to live with it."

The

article

about the Federal Supreme Court ruling is

here.

Events focus on genocide awareness

Film screenings, exhibits on display around the Valley

by Luci Scott - Mar. 25, 2012 09:18 PM

The Republic | azcentral.com

April is Genocide Awareness Month in Arizona, and it kicks off early with a screening of a documentary, "The Last Survivor," on Tuesday at Arizona State University in Tempe.

One of the film's directors, Michael Kleiman, will be present to talk about the making of the film and how genocide survivors can be helped.

The film, to be screened at 6 p.m. in Room 241-C in ASU's Memorial Union, tells stories of survivors and focuses on genocide prevention and civic activism.

Another film, "Kony 2012," about African war criminal Joseph Kony, will be shown at 7 p.m. April 3 in Room 228 of the Memorial Union.

The film is being presented by the non-profit group Invisible Children, which works to combat the practice of using children as soldiers. This film is longer than the one that has gone viral on the Internet and stirred controversy over its accuracy.

On April 2, Scottsdale Community College will host an interactive event with two features: booths staffed by international groups and Camp Darfur, described as a traveling refugee camp consisting of a group of tents representing previous and current genocides.

The daylong activity will be in the mall west of the Applied Sciences Building.

"It brings attention to the ongoing genocide in Darfur, Sudan," said John Liffiton, co-coordinator, with Larry Tualla, of the college's Honors Program, the host of the activities.

Visitors will learn about modern Darfur as well as such previous mass murders as the Holocaust, the Turks' slaying of Armenians during World War I and mass killings in Cambodia and Rwanda.

"When people think of the Holocaust, they think of World War II, but genocide is still happening today," Liffiton said.

He is a professor in the college's English department and director of the English as a Second Language Program.

Camp Darfur is open to the public April 3-4 at GateWay Community College, 108 N. 40th St.

On April 5, a screening of "Kony 2012" is scheduled for 7 p.m. in the auditorium of Dobson High School, 1501 W. Guadalupe in Mesa. It is free and open to the public.

An entire day of activities for the students will include guest speakers and films as well as the Camp Darfur exhibit, said English teacher Kim Klett, who teaches a course on the Holocaust.

For more information, go to

darfurandbeyond.org.

Secret Service thugs investigage woman for saying "Pretend it's Obama"

Don't these Secret Service thugs have any "real" criminals to hunt down????

Albuquerque cops get $300 to $500 for each person they shoot???

Albuquerque cops get a "bounty" for each person they shoot???

It takes 6 years to fire a cop for murder????

Source

Plea ruling to have little impact in Arizona

Source

Events focus on genocide awareness

Source

Video shows OK police dragging man at airport

Source

Video shows OK police dragging man at airport

Authorities in Oklahoma City are investigating a Feb. 20 incident in which a handcuffed man, accused of trying to sneak past a security checkpoint at Will Rogers World Airport, was reportedly dragged, face-down, by his feet after being tased several times by Oklahoma City Police officers, according to News9.com in Oklahoma.The incident was captured by surveillance cameras.

“What we have seen on the video caused us some concern,” said Captain Dexter Nelson with the Oklahoma City Police Department. “That’s why we launched the investigation.”One of the officers was placed on restrictive duty, according to reports. The charges against Heidebrecht — trespassing, disorderly conduct and resisting arrest — were dismissed.A police report from February 20 showed James Heidebrecht tried to enter a secure area. When an officer confronted Heidebrecht, the suspect claimed he was part of the CIA and was at the airport to meet presidential candidate Newt Gingrich.

The man can be heard in the security footage claiming, “I’m with the CIA.” In the police report, officers described Heidebrecht as combative. The security video shows one officer shoved Heidebrecht to get the man away. That was then an officer fired his taser, striking Heidebrecht. The audio from the recordings revealed that officers repeatedly commanded the suspect to “put your hands behind your back.”

Videotaping the police is punishable by a beating????

Source

Police committee OKs $100,000 settlement with videographer

By Brian Haynes

LAS VEGAS REVIEW-JOURNAL

Posted: Mar. 26, 2012 | 10:23 a.m.

The Metropolitan Police Department will pay $100,000 to a Las Vegas man who said he was beaten by an officer as he shot video from his driveway.

The police Committee on Fiscal Affairs unanimously approved the settlement with Mitchell Crooks on Monday.

The payment settles the federal civil rights lawsuit filed by Mitchell Crooks, whose video of the confrontation with officer Derek Colling became an Internet hit. Crooks filed his lawsuit in November, eight months after his run-in with Colling on a dark cul-de-sac in the southwest valley.

Crooks was videotaping police from his driveway the night of March 20, 2011, as officers investigated a burglary across the street near East Desert Inn Road and South Maryland Parkway. As Colling was driving away, he stopped his car, got out and approached Crooks.

He ordered Crooks to stop filming, and when Crooks refused, Colling beat him, according to the lawsuit.

Crooks was arrested for battery against an officer, trespassing and resisting arrest, but the charges were dropped.

An internal investigation concluded that Colling, a six-year veteran, violated several department policies. Police would not release the specific policy violations. Sheriff Doug Gillespie fired Colling in December. Colling is fighting his termination.

Contact reporter Brian Haynes at bhaynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0281.

Cops demonizing Trayvon Martin to justify his murder???

Source

Police in Florida demonizing slain son, mother says

Mar. 26, 2012 12:35 PM

Associated Press

SANFORD, Fla. -- Trayvon Martin had been suspended from school for marijuana when the unarmed teenager was shot to death by a neighborhood watch volunteer, a family spokesman said Monday.

Martin, 17, was suspended by Miami-Dade County schools because traces of marijuana were found in a plastic baggie in his book bag, family spokesman Ryan Julison said. Martin was shot Feb. 26 by George Zimmerman while he was visiting Sanford with his father.

Martin's mother, Sybrina Fulton, and family attorneys blamed police for leaking the information about the marijuana to the news media in an effort to demonize the teenager. [This isn't the first time cops demonized their enemies and it won't be the last]

"The only comment that I have right now is that they killed my son and now they're trying to kill his reputation," Fulton told reporters. [Sadly I suspect the woman is correct about that!!!]

The Sanford Police Department insisted there was no authorized release of the suspension information but acknowledged there may have been a leak within the agency. City Manager Norton Bonaparte Jr. said the source of the leak would be investigated and the person responsible could be fired. [But the person responsible almost certainly won't be found]

"We do not condone these unauthorized leaks of information," Bonaparte said. [Are his fingers crossed???]

Martin family attorney Benjamin Crump said the link between the youth and marijuana should have no bearing on the probe into his shooting death. State and federal agencies are investigating, with a grand jury set to convene April 10.

"If he and his friends experimented with marijuana, that is completely irrelevant," Crump said. "What does it have to do with killing their son?" [Nothing, nada, zippo! But the cops will use any lame excuse to demonize him to justify the murder in the eyes of the public!]

Also Monday, the state Department of Juvenile Justice confirmed that Martin does not have a juvenile offender record. The information came after a public records request by The Associated Press.

Zimmerman, 28, claimed he shot Martin in self-defense and has not been arrested. Because Martin was black and Zimmerman has a white father and Hispanic mother, the case has become a racial flashpoint that has civil rights leaders and others leading a series of protests in Sanford and around the country.

In another development, city officials named a 23-year veteran of the Sanford police department as acting chief. The appointment of Capt. Darren Scott, who is African-American, came days after Chief Bill Lee, who is white, temporarily stepped down as the agency endured withering criticism over its handling of the case.

"I know each one of you -- and everyone watching -- would like to have a quick, positive resolution to this recent event," Scott told reporters. "However, I must say we have a system in place, a legal system. It may not be perfect but it's the only one we have. I urge everyone to let the system take its course." [I think the cops are saying the system sucks so don't complain?]

Professional football players Ray Lewis and Santonio Holmes are joining civil rights leaders Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton at a rally in Sanford later Monday. Also joining the rally are comedian Sinbad and leaders from the Urban League and ACLU.

Commissioners with the city of Sanford will also meet Monday for the first time since they gave Lee a no confidence vote.

Martin's parents plan to address them. The meeting was moved from City Hall to the Sanford Civic Center to accommodate the expected large crowd.

Martin was returning to his father's fiancee's home from a convenience store when Zimmerman started following him, telling police dispatchers he looked suspicious. At some point, the two got into a fight and Zimmerman pulled out his gun.

Zimmerman has not spoken in public about the shooting. His lawyer, Craig Sonner, has denied there was any racial motive in the shooting.

A man identified as a friend of Zimmerman said Monday the neighborhood watch volunteer would tell the teen's parents he's "very, very sorry" if he could.

Speaking on ABC's "Good Morning America," Joe Oliver said George Zimmerman is not a racist and has virtually lost his own life since the shooting.

"This is a guy who thought he was doing the right thing at the time and it's turned out horribly wrong," Oliver said.

On NBC's "Today" show, Oliver said he had spoken with Zimmerman's mother-in-law, who said Zimmerman was remorseful.

"I learned that he couldn't stop crying for days after the shooting," Oliver said.

Sanford cops continue to demonize Trayvon Martin

SourcePolice investigated Trayvon Martin over jewelry

Mar. 27, 2012 03:55 PM

Associated Press

SANFORD, Fla. -- Women's jewelry and a watch found in Trayvon Martin's school backpack last fall could not be tied to any reported thefts, the Miami-Dade Police Department said Tuesday.

The Miami Herald in its Tuesday editions reported that it had obtained a Miami-Dade Schools Police Department report that showed the slain teenager was suspended in October for writing obscene graffiti on a door at his high school. During a search of his backpack, the report said, campus security officers found 12 pieces of women's jewelry, a watch and a screwdriver that they felt could be used as a burglary tool.

Martin's fatal Feb. 26 shooting in Sanford, Fla., by neighborhood watch captain George Zimmerman has caused a national firestorm. His family and people at rallies all over the country have demanded the arrest of Zimmerman who says he shot the unarmed 17-year-old in self-defense. Martin was black and Zimmerman's father is white and his mother, Hispanic. Martin's family and their supporters believe race played a part in the decision not to charge Zimmerman.

The Herald reported that when campus security confronted Martin with the jewelry, he told them that a friend had given it to him, but he wouldn't give a name. The report said the jewelry was confiscated and a photo of it was sent to Miami-Dade Police burglary detectives. Miami-Dade school officials declined Tuesday to confirm the report when contacted by The Associated Press, citing federal privacy laws regarding students.

Miami-Dade Police confirmed that it had been asked by school police to help identify the property taken from Martin's backpack. It notified school police that the jewelry did not match any that had been reported stolen.

Martin had previously been suspended for excessive absences and tardiness and, at the time of his death, was serving a 10-day suspension after school officials found an empty plastic bag with marijuana traces in his backpack.

His parents and their lawyer, Benjamin Crump, have said such reports are irrelevant to the shooting and part of an attempt to demonize Martin. Crump did not return calls to The Associated Press on Tuesday.

Meanwhile, black Democratic members of the Florida Legislature are demanding that a special session be called to consider whether to repeal the state's seven-year-old "Stand Your Ground" law, which eliminated a person's duty to retreat when threatened with seriously bodily harm or death.

Sanford police have cited the law as the reason Zimmerman wasn't arrested after the shooting. They are also demanding that a task force appointed by Gov. Rick Scott to examine the shooting and any changes needed to state law begin work immediately instead of waiting for the police investigation to conclude.

"Whether self-defense was a legitimate factor, the law remains intact -- with all the same components still in place for more killings and additional claims of self-defense, warranted or not," state Sen. Chris Smith wrote in a statement to the governor. "...I'm sure you will agree that delaying the work of the task force -- possibly up to one year or longer -- suits no purpose other than to allow more tragedies to unfold."

But Scott and other Republicans have insisted that the state should wait until ongoing police investigations are completed.

Republican Rep. Dennis Baxley, one of the sponsors of the law, said that "when things have cooled off a little bit I think it's worthy to sit down and say is there legislation that is needed."

In Sanford Tuesday, the city manager said that hiring an outsider to run the police department is a priority to help cool tensions caused by Martin's death and the investigation.

Manager Norton Bonaparte said officials were working with the nonprofit group Police Executive Research Forum to identify potential candidates.

Police Chief Bill Lee temporarily stepped down after outrage erupted over the police department's handling of the shooting.

Darren Scott, a 23-year veteran of the Sanford Police Department, was named acting chief. Lee is still employed with the department and receiving his salary.

At a news conference Tuesday, Bonaparte and Scott refused to answer any questions about an information leak to the media. The leak contained an account by Zimmerman that said Martin was the aggressor in a fight leading up to the shooting. Officials have said they will investigate where the leak came from.

"We have a legal system in place and we ask that people let it take its course," Darren Scott said. "I am concerned with everyone's concerns, but I will not comment on the investigation."

"It was not known whether any of those caught were terrorists" - I think it is rather well documented that the Patriot Act has caught almost NO terrorist whatsoever. I think the offical statistics are about one half of one percent of the people arrested are alleged terrorists. Almost all of the people arrested as a result of the unconstitutional Patriot Act are drug dealers.

Lawmakers call airport screeners ineffective, rude

Mar. 26, 2012 02:52 PM

Associated Press

WASHINGTON --House members of both parties on Monday teed off against the agency in charge of airport and port anti-terrorist screening, saying it uses ineffective tactics, wastes money on faulty equipment and treats travelers rudely.

"We're not cattle," said Rep. Gerald Connolly, D-Va., adding that 'barking orders" undermines the good work of the Transportation Security Administration.

TSA officials told a hearing that airport screening is getting better for U.S. travelers, because the agency is moving away from a one-size-fits-all system. Instead, the TSA is expanding programs to identify travelers posing a risk, while allowing those who provide personal information in advance to go through a fast line.

A report by the Government Accountability Office, Congress' investigative agency, agreed with lawmakers that several key programs of the TSA have been flawed.

Stephen Lord, director of the GAO's homeland security program, offered the investigators' assessment of the TSA at a joint hearing of the committees on Transportation and Infrastructure; and Oversight and Government Reform: The findings:

--TSA deployed its Screening of Passengers by Observation Techniques program nationwide before determining whether it was valid to use behavior and appearance to reliably identify passengers posing a risk. It was not known whether any of those caught were terrorists. Rather, the program nabbed illegal aliens, drug offenders, those carrying fraudulent documents and people with outstanding warrants.

--While 640 full-body scanners were deployed to detect both liquids and metals, some of the units were not being used regularly, thereby decreasing benefits of machines that cost $250,000 each to buy and install.

--The Transportation Worker Identification Credential program used for 2.1 million workers at ports and on ships has been unable to provide reasonable assurance that only qualified individuals can acquire the card.

Christopher McLaughlin and Stephen Sadler, two TSA assistant administrators, emphasized that help is on the way, but spent most of the hearing fending off lawmakers' angry comments.

McLaughlin said TSA is working on easing the checkpoint experience for children and senior citizens, including ending a requirement for them that shoes be removed and conducting less intrusive pat downs.

He said that the TSA Pre-Check system, the fast-lane screening program, has been expanded to a dozen airports and more than 500,000 passengers and received positive feedback. He said any U.S. citizen in the Customs and Border Protection's trusted traveler programs will qualify for streamlined screening when flying from 14 international locations.

None of this satisfied the committee members.

Oversight Chairman Darrell Issa, R-Calif., said TSA wasted millions of taxpayer dollars developing equipment that didn't work, leaving in its wake "a dire picture of ineffectiveness."

Rep. Tom Petri, R-Wis., said TSA treated traveling Americans "like prisoners."

The chairman of the Transportation Committee, Republican John Mica of Florida, said faulty equipment was hauled away from a storage site "as our investigators were appearing on the scene."

And Issa read comments from Americans who accepted his Internet invitation to write about their experiences on the committee's Facebook site.

A Marine in dress blues said he was forced to remove his trousers because his shirt stays spooked a screener. A disabled person complained about constant groping. So did a traveler with a medical device that can't go through machines generating radiation. And a 61-year-old traveler who had an artificial leg since age 4 gave up traveling, tired of having her breast checked rather than her leg.

Rep. Steve Cohen, a Democrat from Memphis, said screeners went through all the items of a woman known as one of the richest in his town.

He said it should have been obvious from her expensive possessions that "this woman wants to live."

L.A. County sheriff's officials may have overpaid for work, equipment

By Robert Faturechi, Los Angeles Times

March 27, 2012

Los Angeles County sheriff's officials overpaid a private contractor nearly $11 million for work that wasn't needed and aircraft equipment they already had, according to allegations in a sheriff's memo obtained by The Times.

The internal report recommended that supervisors within the emergency air support division be investigated for potential conflicts of interest and violations of county purchasing rules. Aero Bureau supervisors, the report states, allowed the Carlsbad avionics firm, Hangar One, to bill for unjustified expenses while outfitting a fleet of helicopters.

Sheriff's officials paid the firm for 3,888 hours of installation work for each aircraft. Compared with the industry standard, the internal memo states, that's eight times more man-hours than needed.

"This per aircraft amount cannot be justified," sheriff's Sgt. Richard Gurr wrote in the report, calling the charges "extremely excessive."

In other instances, Aero Bureau officials purchased special equipment from the firm despite already having a well-stocked inventory. The department spent almost $500,000, for example, on 42 night-vision goggles when the dozen they already had were "sufficient to support any LASD mission." On another occasion, they picked up 20 sets of water safety gear when none were needed.

The division made six-figure purchases without the required approval of the Board of Supervisors. "They have purposely bypassed the established purchasing code protocols," the memo states. "LASD Aero Bureau managers have potentially violated numerous L.A. County Codes and Guidelines."