|

Source

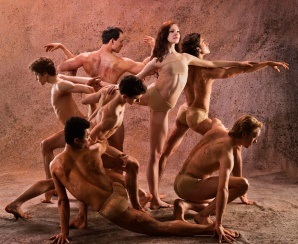

5/2-26: Ballet Arizona's 'Topia' at Desert Botanical Garden Troupe pirouettes to Ib Andersen ballet on garden stage by Richard Nilsen - Apr. 28, 2012 03:39 PM The Republic | azcentral.com Making ballet is different from what you might expect. For one thing, it's slow. Ib Andersen is standing in the middle of Ballet Arizona's studio with dancer Roman Zavarov. They are working on the beginning of the finale to the company's new ballet, "Topia," which will be presented outdoors at the Desert Botanical Garden beginning Wednesday, May 2. Andersen does not speak much, but rather shows what he wants, and moves around the space in a circle with Zavarov miming each step, as Beethoven's "Pastoral" symphony plays on the loudspeaker. "I want something that is simple," he says later. "I want to let the music speak here." After 45 minutes of repetition, the two have worked out perhaps eight bars of music. A few seconds have been created, and the next 10 minutes of melody and harmony await. Andersen turns his attention to the corps de ballet, the eight ballerinas who enter as the movement's main tune begins. They now occupy his focus, and he demonstrates what they will do, changes his mind, tries another tack and then adds a new fillip. Choreography, a la Ib Andersen, is a moment-by-moment invention. "Really, if you do 20 seconds of choreography in three hours, that is actually working fast," dancer Elye Olson says. Andersen, by Olson's reckoning, is actually a very fast worker, and, he says, "Topia" is going faster than usual. Already, the first four movements of the symphony have been finished, with only the finale to work on. Filmmaker Bill Fenster is making a documentary about the creation of "Topia," and he has gotten to know Andersen and his working methods. "Ib is very internal," he says. "He listens to the music at home and sees shapes and movements in his mind. "But he doesn't block it out on the weekend. He doesn't come in and say, 'You three, I'm going to have you do three pirouettes.' He has things in his mind, and they're not necessarily men or women. "I talk to him about this. They're dancers; they're shapes. And at one point, the women are doing some very physical stuff -- untraditional, actually catching one of the men. "And that didn't come out of a philosophical sense that women should be strong, or out of something he pre-visualized, but from letting the dance and the music create itself as he goes along." Doing it up big "Topia" is something new for Andersen and Ballet Arizona. It is a 45-minute ballet choreographed not only for outdoor performance but for a large stage, set against the Papago Buttes, where nature, Beethoven and the dancers all vie for our attention. "There is some kind of equilibrium there," Andersen says. "Normally, Beethoven completely overwhelms everything." The composer's music is seldom used for dance; because it demands so much attention itself, there is little room for the dancers. "But being out there in the desert, already overwhelmed with landscape, there is something that can push back against Beethoven," Andersen says. "Beethoven has competition from the environment." At Desert Botanical Garden, a stage is being built, twice as large as the one the company is used to dancing on at Symphony Hall. It's actually two stages melded. This will be ballet in cinemascope. "Everything is so big out there, it didn't make sense to do this dance on a little stage," Andersen says. "It made sense to do it big." This complicates matters for the choreography: Instead of a single focus for the audience, the dancers will spread over a 90-foot area, making it almost more like a three-ring circus. "You can go from one stage to another and can do a lot in between," Andersen says. "You will have multiple focuses. "That's how you look at landscape: Your eyes can only see so much. You look to one side and then another, and your brain puts them together to make a whole picture." New infrastructure More than just a stage, the ballet and garden are building whole new infrastructure for the monthlong production. There will be a catering tent offering food and drink, a cash bar, bathroom facilities and more. Trees are being brought in to block out the traffic on Galvin Parkway. There will be banked seating for those who want to see just the dance, and festival tables for those who want to eat and imbibe during the performance. The dancers will be dressed in minimal costumes that are flesh-colored, so they look almost naked. "Basically naked," Andersen says. "Maybe Greek- or Roman-inspired but just vaguely. "I want it to be that you see the form of the human body; I don't want to have anything that's in the way." And there's a practical consideration. "On top of that, we might be dancing in 90 degrees or more, and it's a quite demanding ballet, and I don't want them to faint onstage. This way we have natural air-conditioning. "I've danced outside in hot weather, at Saratoga Springs (N.Y.). I remember once it was 115 and I almost fainted." Dancer Kenna Draxton isn't worried about the heat, she says. At night it will be less hot, and besides, "Warm is great to start up with, when we're trying to get our bodies warmed up. We're sweating, but that's great. We feel great then." Music is the glue Andersen is well known among dancers and choreographers for his musicality. He always starts with the music. "The glue that holds it all together is the music," Andersen says. Beethoven's "Pastoral" symphony has five movements, with a slow second movement that provides the core of the dance, and a fourth movement that is a thunderstorm, complete with lightning zaps. That gives way to a finale that brings a new sense of repose. Andersen says this is the only Beethoven music he would even consider choreographing to. "This music is the most broad," he says. "It's music that has a clarity to it, a solution at the end, a resolution. There's a great Danish word for it, but that doesn't help. "It's like the sun came out after the storm, and you see everything with a clarity that you've never seen before." That is the part of the music he is working on as he lines up his corps and they perform in a line moving from one end of the stage to the other in the studio. "I don't think I'm there yet, but I think I'm getting there, a little bit. "This movement is one of the most difficult moments in the whole ballet. It's a transition." It's hard for Andersen or the dancers to fully visualize what will be seen onstage. The studio is too small a space. Dancers keep bumping into the walls. "It's a problem," Draxton says, "because we can't experience what it is like on the stage. Here, we're running into each other." At times, they take the whole thing out into the parking lot behind the studio, put the CD into a car's audio player and practice in the larger space, more like the outdoors of the garden. Andersen is taking a chance with this dance, but it gives him an opportunity to grow as an artist; it gives him a challenge. "I just hope, and the whole intent of what we're doing is, in that environment with those Papago Buttes in the back, with trees and the two giant saguaros right behind the stage, you are outside and have stars up there, and Beethoven's music and the stage and the dancing ... I hope that people will feel it to be an extraordinary experience, more than in a theater." |